The End of a Price Era

For decades, Pakistan’s government set the price of its most crucial crop – wheat – shielding farmers from market vagaries and keeping roti affordable. That era is now unraveling. In 2024, a dramatic policy U-turn saw Punjab province deregulate the wheat market, opting not to announce a minimum support price (MSP) or set a procurement target. It was the first time in provincial history that wheat prices were to be left to “free market” forces. The move came on the heels of extraordinary events. After catastrophic floods in 2022 shrank the wheat crop and sent flour prices soaring, the government had rushed to import 3.5 million tonnes of wheat in late 2023. Then, aided by good weather and more area planted, Pakistan harvested a record 31.4 million tonnes of wheat in 2024 – a bumper crop well above national consumption. Paradoxically, that bumper harvest triggered a crisis for farmers. With government granaries already full (carryover stocks exceeded 4 million tonnes) and an IMF-backed mandate to cut subsidies, officials slashed public wheat purchases to just 2 million tonnes – barely one-third of normal. Suddenly, growers who had been encouraged to sow wheat were told to find their own buyers.

The result was plunging farm-gate prices. By April 2024, as the new grain poured in, wheat was selling for only around Rs 2,200–2,800 per 40kg in Punjab’s markets – far below the official support price of Rs 3,900 and even below farmers’ cost of production (estimated ~Rs 3,300–3,400 per 40kg). “How are farmers expected to sell at a loss?” one farmer leader protested, noting government data on production costs. Wheat growers, once protected by state purchases, suddenly faced exploitation by middlemen and price crashes. Anger swept the countryside. In April 2024, farmer organizations like the Pakistan Kissan Ittehad (PKI) threatened protests across Punjab, demanding the government procure at least 5 million tonnes and raise the wheat price to Rs 5,000/40kg. As one PKI leader put it, “We were promised support, but now we’re abandoned.” Police crackdowns on protesting farmers in Lahore – batons swinging against growers in their dusty shawls – only underscored the chaos of a botched transition.

The policy disarray took on a provincial twist. While Punjab “freed” the market (to the ire of its farmers), neighboring Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) initially announced it would buy wheat at the old support price of Rs 3,900 to build its stocks. This led to thousands of tonnes of wheat being trucked from Punjab to KP in search of a better price. But KP’s plan soon unraveled: by June 2024, after buying about 15,000 tonnes, the KP Food Department abruptly stopped purchases, leaving over 2,500 Punjab wheat trucks stranded at KP depot gates. The provincial government, facing budget constraints, backtracked on the Rs 3,900 price, and those farmers were forced to sell their grain at roughly Rs 2,400 in the open market. This fiasco of dueling policies – Punjab’s laissez-faire vs. KP’s short-lived support – revealed a glaring lack of coordination.

By early 2025, the support price regime that had defined Pakistan’s wheat policy since the 1950s appeared to be collapsing. Under IMF pressure to cut subsidies, the federal government and provinces stepped back from price-setting. Officials argued farmers would benefit from a competitive market with more private buyers. But the “free market” came with mixed signals and no safety nets. Farmers were told to accept market prices – yet the government still controlled downstream flour and roti prices to protect consumers. “Sheer hypocrisy,” PKI’s president blasted: “Farmers are denied a fair price, yet flour mills and consumers are still protected by price controls.” Indeed, in 2024 Punjab had even capped the price traders could pay (filing FIRs against those buying above Rs 2,675/maund) to prevent flour inflation – effectively preventing farmers from getting higher rates. Such contradictions left everyone frustrated.

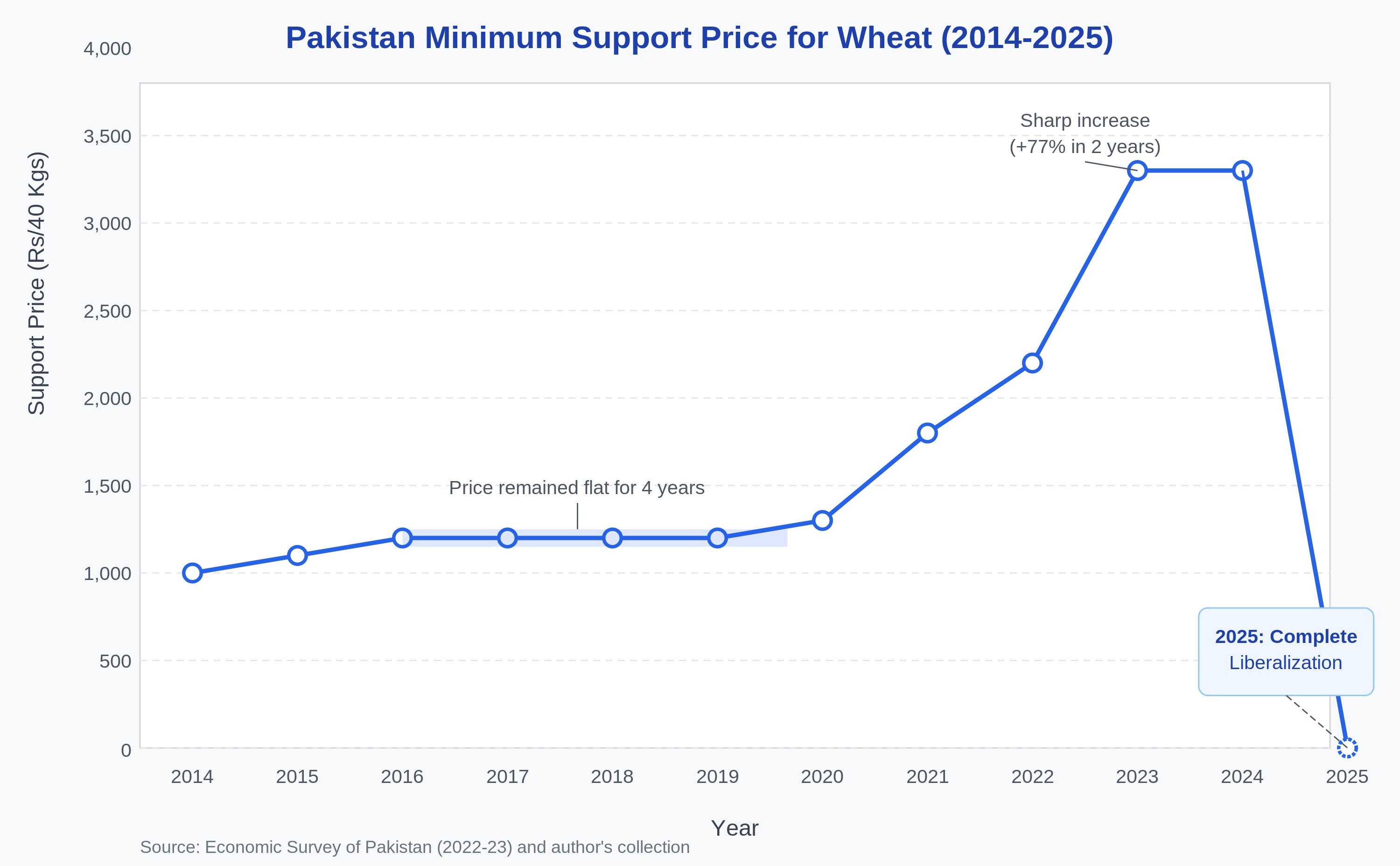

Pakistan’s Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat remained mostly flat through the 2000s and early 2010s, before a series of increases from 2019 onwards. By 2023, the MSP had risen sharply to Rs 3,900 per 40kg, but was abolished in 2025 under IMF reforms. This turning point marks the end of decades of government price protection for wheat, raising new questions for the future of farming and food security.

Thus, the support price saga – from deregulation to farmer backlash – has illuminated deep cracks in Pakistan’s wheat policy. A system that long balanced farmer and consumer interests is now in flux, with unclear transition planning. As Pakistan grapples with this upheaval, it prompts a broader reflection: what does this turmoil reveal about the country’s long-standing wheat policy and its wider effects on agriculture and food security? The following sections examine why wheat became the crop we “can’t let go,” whether MSP cushioned farmers into complacency, how structural realities constrain choices, and what a viable path forward could look like in a post-MSP era.

Why Wheat? The Crop We Can’t Let Go

Wheat isn’t just another crop in Pakistan – it’s the lifeblood of the national diet and a pillar of politics. As Pakistan’s principal food grain, wheat covers about 66% of the area under food crops and makes up 74% of the country’s total grain production. It contributes roughly 2–3% to national GDP and nearly 14% of agricultural value-added. More importantly, wheat provides an estimated 72% of the average Pakistani’s caloric intake. In plain terms, the daily roti or chapati on the table is usually made of wheat flour. Ensuring a stable supply of affordable wheat has therefore been synonymous with food security. Memories of the 1960s “Green Revolution” still linger, when high-yield wheat varieties helped Pakistan feed a growing population. Wheat self-sufficiency became a strategic goal and a point of pride.

To achieve this, the government has historically taken an active role from farm to fork. Since the 1950s, Pakistan maintained a Minimum Support Price (MSP) system for wheat. Each year before the rabi planting season, authorities announce a guaranteed price at which government agencies will purchase wheat from farmers at harvest. State entities like the provincial food departments and PASSCO (Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation) then procure a significant portion of the crop (around 20% in normal years) into public granaries. This intervention aimed to serve a dual mission: protect farmers’ incomes by assuring them a buyer at a fair price, and stabilize consumer supply by building stocks that can be released to flour mills to moderate prices. In effect, the government has acted as the market “maker” for wheat – buying low in harvest season to support farmers, and later selling wheat to mills (often at subsidized rates) to keep flour prices in check through the year.

Over time, this heavy involvement did help Pakistan meet its wheat needs. Domestic production, boosted by MSP incentives and input subsidies, kept pace with a fast-growing population. From less than 10 million tonnes in the 1960s, wheat output rose to around 25–28 million tonnes in the 2010s, roughly matching annual consumption. By the early 2000s, Pakistan was broadly self-sufficient in wheat in most years. This policy of “food autarky” was seen as essential – the country could ill afford dependency on foreign wheat given the vagaries of international markets and limited foreign exchange. And indeed, whenever wheat supplies ran short, it created turmoil: in early 2020 and again in 2022, wheat flour shortages led to long breadlines and public anger, pushing the government to intervene with emergency imports and crackdowns on hoarders.

Culturally and politically, wheat carries enormous weight. It is the one crop successive governments dare not neglect. An abundant wheat harvest is touted in press conferences as a government success; a wheat price spiral is treated as an existential crisis. The MSP, in this context, became not just an economic tool but a social contract: farmers would ensure the nation’s bread supply, and the state in return would guarantee farmers a reasonable livelihood from wheat. This contract has persisted even as other sectors liberalized. For example, while many fruits and vegetables see volatile open-market pricing, wheat’s price was administratively managed to avoid any chance of roti becoming unaffordable.

However, this “can’t let go” attachment to wheat also bred a degree of inertia. By treating wheat as untouchable, Pakistan may have inadvertently sidelined other crops and deeper reforms (a point we explore soon). Still, one can understand the reluctance to change – wheat has been the safety crop for the nation. As one analyst noted, the heavy wheat intervention did succeed in its core aim: increasing domestic production to meet national needs. The country hasn’t faced mass hunger for wheat in decades, which is no small achievement for a nation of 240+ million. Moreover, wheat is critical for rural employment and incomes in the major growing zones of Punjab and Sindh. It’s planted on over 9 million hectares annually, providing work to millions of farming families.

In short, Pakistan’s economic, food security, and political calculus have long revolved around wheat. The MSP system and government procurement were the linchpins holding that calculus together – balancing urban consumers’ demand for cheap flour with farmers’ need for decent income. Wheat became the crop we cannot let go because letting it go felt akin to risking both “roti for the people” and “rosi for the farmer” (livelihood for the farmer). This context helps explain why the events of 2023–24 were so convulsive. By pulling back state support for wheat, the government rattled a pillar that had supported Pakistan’s food system for generations. To understand the fallout, we must examine how that pillar both propped up and perhaps constrained our agriculture.

Has MSP Made Wheat Too Comfortable?

One critical question is whether the long-running minimum support price cushion made wheat farming “too comfortable” – a low-risk, low-innovation enterprise. The MSP shield was meant to encourage wheat production, but over decades it may have also induced complacency and inefficiencies among producers. There are several ways this played out:

- Stagnant Yields and Innovation: A guaranteed buyer at a fixed price can dull incentives to improve productivity or quality. Farmers know they can sell whatever they harvest at the MSP, so the drive to push yields higher may weaken if the support price doesn’t reward extra effort or better grain. Indeed, Pakistan’s wheat yields have plateaued at modest levels (around 2.8 tons/ha on average) despite favorable conditions. The World Bank observes that our wheat yields remain low and that “distorted incentives have hindered investment in the sector.” Removing MSP, it argues, could spur farmers to adopt better technologies because they’d need to compete and maximize profits. Under the MSP regime, many farmers stuck with the same seed varieties and traditional methods year after year; there was little competitive pressure to change. Furthermore, grain quality took a backseat – government procurement cares only about quantity (tonnage), not protein content or baking quality. In a market-driven system, by contrast, millers might pay premiums for higher-quality wheat. Under MSP, that signal was absent. So, the support price may have bred a “good enough” mentality: as long as you hit the average yield, you’re safe, with no incentive for excellence.

- Discouraging Diversification to Higher-Value Crops: When one crop is a sure bet, farmers are less inclined to experiment with alternatives. Wheat’s MSP effectively set a floor on returns for the winter (rabi) season. A farmer could be confident of getting, say, Rs 1,950 per 40kg in 2020, then Rs 2,200 in 2021, then Rs 3,900 by 2023 as the government raised prices during crises. This steady increase made wheat an attractive, or at least reliable, option relative to other crops like oilseeds, pulses, or vegetables, which had no such price guarantees. As a Dawn editorial noted, the policy “discourages farmers from diversifying into value-added crops.” Why grow, say, canola for an uncertain market when wheat offers assured buyers and government support? Over time, Punjab and Sindh’s irrigated plains became locked in a wheat-centric rotation each winter. Even in areas where another crop might have yielded higher profits, the MSP’s safety net nudged farmers to stick with wheat – it was the default choice, season after season. This has arguably kept Pakistani agriculture more subsistence-oriented, focusing on filling the wheat basket rather than optimizing farm income through crop variety.

- Anchoring Farming Decisions to One Crop: Thanks to MSP, wheat turned into the “comfortable old shoe” of Pakistani farming – dependable but not dynamic. Many farmers plan their entire year around the wheat cycle, often to the exclusion of potentially more lucrative uses of land. Wheat’s harvest timing and guaranteed offtake made it a cornerstone: for example, cotton growers in Sindh or Punjab ensure they clear fields in time for wheat; smallholders everywhere allocate whatever land they can to wheat for security. This ubiquity means other opportunities (like planting winter vegetables for urban markets or sowing fodder for a dairy enterprise) are sometimes passed over. Wheat became almost an end in itself. One could argue it turned into a low-risk, low-reward monoculture. The MSP virtually ensured wheat would cover its costs – but also capped the upside. In years of global price booms, Pakistani farmers didn’t fully benefit because domestic prices were fixed. Conversely, in glut years, farmers were insulated from a price crash. This stability, while comforting, also meant that farming as a business stagnated; the bold entrepreneurship of shifting to significantly higher-value crops was rarely seen. Wheat was king, and MSP its throne, and few farmers dared – or needed – to dethrone it.

These effects suggest that the MSP system, while providing important protections, also created dependency and inertia. Farmers organized their practices around government signals instead of market signals. When fertilizer prices rose or climate threats loomed, the typical response was to lobby the government for a higher support price or subsidy, rather than to diversify or innovate to reduce costs. In economic terms, MSP can create a moral hazard – the expectation of a bailout or fixed price might reduce the urgency to become more efficient.

It’s important to note that this “comfort” was not equally shared by all farmers. Larger producers, who had surplus to sell after meeting their own needs, benefited most from selling hefty quantities at the MSP – they arguably had the luxury to be complacent and still profit. Small farmers, on the other hand, often could not even sell to the government (due to limited surplus or access), and ended up selling to middlemen at slightly lower than MSP rates. Even so, the MSP set a benchmark that helped even those smaller sellers bargain for a bit more. Collectively, though, Pakistan’s wheat sector settled into a steady state: production rose slowly, yields inched up only gradually, and crop patterns remained wheat-heavy. The support price had achieved its original purpose of ample wheat supply, but at the cost of flexibility and dynamism. Now that this comfortable regime is being upended, the pains and possibilities of change are coming sharply into focus.

Structural Constraints: Fragmented Farming

If MSP made wheat an attractive habit, structural constraints in Pakistan’s farming system have made it a necessity for many. Even without policy-induced comfort, millions of farmers have stuck with wheat because their landholdings, resources, and market access leave them little choice. Pakistan’s agriculture is dominated by small, fragmented farms that struggle to adopt high-value or capital-intensive alternatives.

Land distribution in Pakistan is highly skewed. A tiny elite of big landlords (about 2% of farmers) control 40–45% of farmland, while the remaining 98% of farmers share just over half the agricultural land. Within that majority, there are about 7.4 million smallholders cultivating less than 12.5 acres (5 hectares). In fact, over 90% of all farmers are smallholders by Pakistani standards (owning under 12 acres). Many hold far less – 5 acres, 2 acres, or a few kanal. Often their land is divided into multiple tiny plots inherited over generations. Such fragmentation has several implications:

-

Limited Mechanization and Modernization: Small plots and limited capital mean low mechanization levels. It’s uneconomical for a farmer with, say, 5 acres (perhaps split into a couple of fields) to own a tractor or combine harvester. While tractor hiring services exist, many small farmers still prepare land with rudimentary tools and harvest manually. The adoption of modern farm machinery remains “low, particularly among small landholding farmers”. This translates into labor inefficiencies and yield gaps. For example, delayed harvesting due to labor shortages can cause losses. Precision agriculture tech (drip irrigation, GPS-guided equipment) is largely out of reach. In this context, wheat – which can be grown with relatively basic techniques – fits the small farmer’s capacity. More delicate or input-intensive crops might be impractical. The monocropping of staples like wheat is partly a result of these mechanization and technology constraints.

- Weak Investment in Inputs and Methods: With such small land, incomes are low and cash flow tight. Many smallholders can barely afford recommended levels of fertilizer or quality certified seed. Credit access is a major barrier – formal loans require collateral and paperwork, so farmers rely on informal lenders or dealers with high interest, eating into profits. This perpetuates a cycle of low investment and low returns. Advanced methods (like controlled irrigation, laser land leveling, or integrated pest management) are rare among subsistence farmers. These practices often need upfront investment or knowledge that poor farmers don’t have. So, farmers stick to the basics: save seed from last year, apply whatever manure or affordable fertilizer they have, pray for rain. Wheat, again, suits this scenario because it’s relatively hardy and straightforward. It will usually give you at least some grain even in a low-input situation. A more sensitive cash crop might fail outright if not properly managed. Small farmers thus often plant wheat to ensure something rather than risk a specialty crop and end up with nothing. The MSP historically guaranteed that even a modest wheat harvest could be sold at a baseline price, making it a safer bet than, say, a failed attempt at tomatoes or chilies.

- Risk Aversion and Lack of Diversification: Small landholding not only limits capacity, it magnifies risk. If you have 50 acres, you might experiment on 5 acres with a new crop; if you have 5 acres total, you’d be gambling the family’s food supply and income on any unproven venture. This leads to highly conservative farming choices. Diversification into other crops or farm enterprises is constrained by fear of failure – and for good reason. A pest outbreak or market glut in an alternate crop could ruin a small farmer, whereas wheat rarely fails completely and always has some market. Moreover, many small farms are in a subsistence mode: they prioritize growing staples (wheat in winter, maybe rice or maize in summer) to feed their family first. Any surplus for sale is a bonus. For these households, wheat farming isn’t a profit-maximizing strategy but a survival strategy. It provides the flour that will sustain them through the year, and only if there’s extra do they think of cash income. With such an outlook, moving away from wheat is not just an economic decision but a food security decision at the household level. They will keep planting it as insurance, even if returns are lower than another crop, because you can eat wheat but you can’t eat cotton or sugarcane.

Additionally, a heavily staffed government procurement and distribution apparatus for wheat (the Food Department, PASSCO, storage facilities, etc.) has historically made marketing wheat relatively easy, even for a small farmer. In contrast, there are fewer institutional buyers for alternative crops. A subsistence farmer knows he can take wheat to the local procurement center or the village trader each April. If he tried chickpeas or canola, finding a buyer might be harder. The lack of efficient markets for other crops further binds farmers to wheat.

In essence, Pakistan’s agrarian structure – small farms with low productivity and high vulnerability – has been both a cause and effect of wheat-centric policies. The MSP gave smallholders a security blanket, but it also perhaps delayed confronting these structural problems. Land consolidation or cooperative farming models (which could improve efficiency) haven’t progressed much. Without addressing such fundamentals, simply removing MSP could leave these farmers extremely exposed (as we saw in 2024). It’s like taking training wheels off a bicycle that’s missing a pedal. Thus, any rethinking of wheat policy must go hand-in-hand with helping farmers overcome structural hurdles – or else the safest path for them will continue to be wheat, whether or not it’s profitable.

The Psychology of “Safe” Farming

Beyond economics and land size, there is a psychological dimension to Pakistani farmers’ attachment to wheat. Generations of experience have ingrained wheat as the default and “safest” choice – a crop that may not make you rich but almost certainly won’t leave you empty-handed. This mindset has proven remarkably resilient, even when profits are minimal.

For many farmers, wheat cultivation is as much about tradition and security as it is about income. It’s what their fathers and grandfathers planted; it’s the crop around which village routines and rituals revolve (the communal threshing, the division of grain, etc.). Planting wheat provides a sense of continuity and reliability in a very uncertain profession. Come what may – drought, flood, price fluctuations – a wheat crop will usually provide at least some grain to fill the family’s flour bins. In a country with limited rural social safety nets, that matters enormously. One small farmer from Khanewal noted that he has no storage capacity and must sell his wheat right after harvest at low prices, but “if I don’t earn from my harvest, how can I sow my next crops?”. This illustrates the cycle of dependency: wheat sales, however meager, finance the next season’s planting. Breaking out of that cycle feels risky.

Wheat has effectively become a “breakeven side job” for many rural households. Consider a peasant with 4 acres: the wheat he grows might barely cover his costs, or yield only a tiny profit, but it provides a year’s supply of atta (flour) for the family. Meanwhile, actual cash needs are met by other means – perhaps a family member working in the city, or income from livestock, or day labor. In such cases, wheat farming is not viewed primarily as a commercial enterprise; it’s more like a subsistence backbone, a part-time venture to ensure food security. Interviews suggest that small farmers often consume a large portion of their wheat output themselves. Studies show Pakistani smallholders typically eat or save over half of their wheat harvest (for home use, seed, animal feed), selling only a little to the market. So a price decline hurts them, but not as acutely as it does a medium-scale farmer who sells most of his crop. This consumption-oriented mindset reinforces wheat’s status as the safe crop – you can always fall back on eating it. By contrast, if a farmer devoted land to, say, onions or chilies hoping for profit and the crop failed or prices collapsed, he might have neither cash nor food.

Even when wheat yields slim profits, farmers stick with it because it’s familiar and trusted. New crops or farming methods are viewed with caution. The psychological cost of failure looms large. It’s telling that when wheat prices crashed in 2024, many farmers’ first reaction was not to vow never to grow wheat again, but rather to demand the government fix the situation. They protested for a higher support price or for resumption of procurement. Some even threatened civil disobedience if MSP was not restored. This indicates that farmers would prefer wheat remain viable (with government help) than switch away from it. It’s a dependency that has been cultivated over years: rather than diversify, farmers lobby for wheat price support, reinforcing the cycle.

That said, the 2023–24 market shock did plant seeds of doubt. Would farmers have moved away from wheat if not for these shocks? Probably not in large numbers – inertia was strong. But after suffering heavy losses, a segment of farmers began to consider alternatives. Agriculture experts observed that farmers might switch 10–20% of their wheat area to high-return oilseeds in the next season, having been jolted by the low wheat prices. Indeed, the federal government and provinces started urging farmers to plant canola, sunflower, and mustard in late 2024, offering subsidies on oilseed cultivation. Some farmers likely acted on these signals, if only as a partial hedge. But notably, many still planted the bulk of their land with wheat – a testament to how deeply entrenched the wheat habit is. Even when betrayed by policy, farmers weren’t going to abandon their staple overnight.

Another telling comment came from farmer leaders in 2025: if prices remained unfair, “farmers would be better off growing wheat only for household needs instead of contributing to national food security.” In other words, in the worst case, they’d shrink production but still grow wheat for themselves. The idea of not growing wheat at all is almost inconceivable to many; the idea of growing it solely for subsistence is seen as a form of protest or last resort. This underscores wheat’s dual role – it is both a commercial crop and the primary food source. That duality makes farmers emotionally reluctant to drop wheat completely.

Finally, there’s a cultural psychology at play: wheat farming is tied to notions of being a true farmer in Pakistan’s breadbasket regions. It’s a matter of pride to bring in a good wheat harvest. Government campaigns have long extolled farmers as providers of the nation’s food. For example, in late 2023, politicians (like Maryam Nawaz in Punjab) encouraged farmers to grow more wheat with promises of better returns. This public encouragement, followed by a policy pullback, left farmers feeling betrayed. The emotional rollercoaster – from being hailed as heroes feeding Pakistan to suddenly being told to face the market alone – was jarring. Farmer protests and speeches were rife with words like “injustice” and “betrayal”. These are emotional terms, not just economic. They reflect how wheat and MSP had become part of the moral economy of rural Pakistan. Removing MSP wasn’t just about money; it felt to farmers like a breach of faith by the state.

In summary, wheat has been the psychological safety crop: reliable, edible, culturally valued, and supported by policy. This has made farmers inherently risk-averse to moving away from it. Changing this mindset will likely require time, education, and demonstration of success in other crops – and even then, many will keep at least some wheat because of its unique security function. The challenge for policymakers is to provide new forms of security (e.g. crop insurance, assured markets for other crops) so that farmers feel safe to diversify. Otherwise, the default psychology will remain: “When in doubt, grow wheat.”

Policy Without a North Star?

If farmers have been torn between old habits and new shocks, the government’s wheat policy has been no less conflicted. The recent support price saga reveals a policy apparatus often driven by short-term panic avoidance rather than long-term vision. In many ways, Pakistan’s wheat policy has lacked a clear “North Star” guiding it; instead, it has oscillated between sometimes contradictory objectives – pro-farmer vs. pro-consumer, free market vs. state control – without a consistent strategy.

One symptom of this is how frequently policy has flip-flopped. In 2022 and early 2023, facing post-flood shortages and public anger over expensive flour, the government was in full crisis-control mode: it poured money into wheat imports and subsidies. Private imports were allowed in mid-2023 to beef up supply, and by early 2023 the government had raised the support price sharply (to Rs 3,900/40kg) to encourage maximum wheat planting. Wheat was a top priority because consumer inflation was at record highs (overall inflation nearly 38% in May 2023) and bread riots were a real fear. Fast forward to early 2024: with a bumper crop looming, the policy priority suddenly flipped to saving fiscal costs and avoiding a glut. The government, under IMF dictates, essentially abandoned the very support price it had championed. As an observer noted, “the government rushed into adopting a free market policy despite having another year to negotiate terms with the IMF”, doing so “without stakeholder consultation”, and leaving farmers vulnerable. Such abrupt shifts – from heavy intervention to hands-off and potentially back again – indicate an absence of steady direction.

This inconsistency stems from trying to juggle multiple, sometimes competing goals:

- Supporting farmers “just enough”: The state doesn’t want farmers to collapse, both for food security and political reasons. Rural livelihoods matter, and farmers form a significant voting bloc. So even in liberalization talks, there are nods to helping farmers. For instance, as Punjab exited wheat buying, it simultaneously announced programs like the Kissan Card (with subsidized inputs and loans) to mollify growers. It’s a bit of a band-aid approach – “we won’t buy your wheat, but here are cheap loans or tractor schemes.” These measures, while positive, didn’t address the immediate price problem. They seemed designed to show that the government still cares, even as it pulls away a long-standing support.

- Controlling consumer prices: At the same time, no government can ignore urban consumers. Wheat flour (atta) is a daily staple for rich and poor alike. Price spikes in atta trigger public outcry and can fuel political unrest. Thus, even while liberalizing the farm side, authorities have kept a tight lid on the consumer side. In 2024, Punjab’s food department outright capped the price that could be paid for wheat in markets (filing police cases against those buying above the cap) to prevent flour prices from rising. They also fixed naan and roti prices to placate consumers hit by inflation. This created a policy paradox: a quasi free-market for farmers but continued price controls for flour. Farmers rightly pointed out the unfairness: “If the government lets market forces decide wheat price, it should also stop fixing flour and roti prices”. By trying to appease both sides – farmers and consumers – the government ended up in a muddle, satisfying neither. Such half-measures illustrate the lack of a coherent game plan. Is the wheat sector being liberalized or not? The answer in 2024 depended on where you stood in the chain.

- Avoiding deeper reforms: The focus on firefighting (farmer protests, flour shortages) has meant that structural reforms are perpetually postponed. Land reforms to consolidate farms or improve tenancy arrangements are politically radioactive (given many legislators are landowners). Investments in research and extension to boost yields don’t grab headlines like a support price hike does. Building crop insurance systems or rural credit networks takes sustained effort, whereas importing a few million tonnes of wheat to calm prices is a quick fix (if one with long-term costs). Time and again, Pakistan’s wheat policy choices have erred on the side of immediate relief over sustainable change. For example, when confronted with a production shortfall in 2019–2020, the government imported wheat and subsidized flour sales – but did not fundamentally change how wheat is produced or marketed domestically. When confronted with farmer discontent in 2021–22, the response was to raise the MSP from Rs 1,400 a few years prior to Rs 2,200 and then to Rs 3,900 by 2023, a massive jump. But no parallel reform was made to, say, reduce the cost of production or ensure timely availability of inputs. Essentially, throwing money (via MSP or subsidies) has been the go-to solution, rather than tackling inefficiencies.

This all came to a head in 2024 when external pressure from the IMF forced a reckoning. The IMF’s 2023 Extended Fund Facility explicitly pushed Pakistan to reduce state intervention in agriculture, citing the huge fiscal burden of wheat operations. To secure bailout funds, the government agreed to measures like abolishing the wheat MSP and possibly even restructuring or closing institutions like PASSCO. These reforms were not born from an internal policy consensus; they were conditions imposed due to a financial crunch. Thus, they lacked local buy-in and preparation. Punjab’s abrupt deregulation in early 2025 was driven in part by these commitments. But the poor timing and planning – coming exactly when a bumper crop hit – turned what might have been a reasonable reform into a farmer crisis. “Those who allowed the import of wheat close to harvest are responsible for this crisis,” admitted Punjab’s food minister in a rare candid statement, though he blamed the previous caretaker government for that decision. An independent analyst noted the government’s retreat from buying wheat “reeks of poor planning and management”. Even if liberalization was the end goal, the way it was done (suddenly, and while still clinging to consumer price controls) was self-defeating.

All these swings have eroded trust. Farmers now do not know what to expect year to year – will there be a support price or not? How much will the government buy? This uncertainty makes it very hard for them to plan cropping decisions and investments. One season of chaos can have multi-year effects, as farmers scale back inputs or plant less wheat the next time (2025’s wheat area did fall after the 2024 debacle, contributing to an estimated 11% drop in production). Farmers’ statements like “we cannot trust the government anymore” reflect a breach in the social contract that had existed. On the other side, consumers and flour millers also face uncertainty – in 2024 they enjoyed cheaper flour due to the surplus, but what if many farmers exit wheat and there’s a shortage next year?

Perhaps the core issue is that Pakistan’s wheat policy has never definitively answered: What is the ultimate objective? Is it to keep wheat prices low for consumers? To keep farmers happy and farming? To avoid budgetary drain? To achieve national self-sufficiency? In theory, a well-crafted policy can try to balance all, but in practice our actions have seesawed, emphasizing one at the expense of the other in alternating turns. The “North Star” has been missing. Contrast this with, say, India, which for better or worse has politically decided that supporting farmers (via MSP and procurement) and maintaining grain self-sufficiency are paramount, and it spends huge sums annually to do so. Pakistan has been less consistent – sometimes emulating that model, other times pulling back in favor of market approaches, but without a stable consensus.

The support price saga lays bare these contradictions. We see a government caught between populism and austerity, between socialist-style intervention and liberal economic reform, without a clear compass. The outcome in 2024 was almost a worst-of-both-worlds: the government ended up violating its IMF terms anyway by intervening in flour prices, angering farmers by abandoning MSP, and still spending billions on past imports and new subsidies, with little long-term benefit to show. It underscores the need for a coherent wheat policy that sets a long-term course and follows it with appropriate support measures, rather than zigzagging in response to each crisis. The next section will discuss what that course might look like – essentially, how to reimagine wheat policy so that Pakistan isn’t stuck in perpetual turmoil, and how to align it with our agricultural realities and future needs.

Where Do We Go From Here? Reimagining Wheat Policy

Pakistan’s wheat policy crossroads is clear: the old MSP-centric system is buckling, yet a pure free-market approach without safeguards could imperil farmers and food security. It’s time to reimagine wheat policy with a balanced, forward-looking strategy. The goal should be to maintain ample wheat supplies and farmer livelihoods without recreating the distortions of the past. This means carefully transitioning to a more market-driven regime, but with robust support structures. Let’s break down the key considerations and reforms needed:

-

Embrace Market Signals – but Manage Volatility: Allowing wheat prices to be set by supply and demand will inevitably bring more price volatility. As we saw, a bumper harvest in 2024 combined with surplus stocks caused farm prices to crash well below the old MSP. Conversely, if a bad drought hits or global prices soar, domestic wheat prices could spike sharply. Volatility is the price of a free market. Yet volatility isn’t necessarily evil – it sends important signals. High prices signal farmers to plant more wheat; low prices signal them to diversify or plant less. In theory, this leads to a more efficient allocation of resources over time. For example, in the free market of 2024, consumers benefited from significantly lower flour prices year-on-year due to abundant supply. Farmers, meanwhile, got a clear message that producing a record wheat crop with no buyer would hurt their pocketbooks – which is prompting some to adjust crop plans. The key is to temper the extremes of volatility. The government should consider maintaining a modest strategic reserve or a mechanism to step in if prices fall below a certain threshold or rise above a pain point for consumers. This could be done with less intrusive tools, like a minimum export price in times of shortage or a floor price for procurement only in disaster years. Overall, however, accepting some degree of fluctuation will lead to clearer market-driven decisions on how much wheat to grow. It’s a trade-off: more short-term uncertainty for potentially greater long-term efficiency. Policy can guide this by ensuring information flows (e.g., transparent crop forecasts) so that farmers can anticipate price trends rather than planting blindly.

-

Facilitate Crop Diversification with Infrastructure: If wheat is no longer a guaranteed money-maker, farmers will naturally look to other crops – and that’s a good thing for the economy. But they can only successfully diversify if the right infrastructure and support for those alternatives are in place. Take the example of oilseeds: Pakistan imports billions of dollars of edible oil each year, while local production of oilseeds (mustard, canola, sunflower, etc.) is minimal. With wheat less attractive, farmers in suitable zones could switch part of their land to canola or sunflower, which often have higher market prices per acre. In fact, after the wheat price crash, experts projected that farmers might convert 10–20% of their wheat area to high-return oilseed crops in the next season. To make this viable, the government should invest in oilseed promotion – ensuring quality seed availability, research into high-yield hybrids, and crucially, that processing facilities (oil mills) are ready to buy the harvest. Similar stories can play out for other crops: more maize for poultry feed (where demand is growing), more pulses like gram and lentils (Pakistan is a big importer, so there’s domestic market potential), or even high-value vegetables and fruits for export. Each of these requires targeted infrastructure: cold storage and transport for perishable veggies, milling and grading facilities for maize, etc. The government can encourage private sector investment in these areas through incentives. One concrete step is to revise import/export policies to encourage local alternatives – e.g., impose or maintain modest import tariffs on edible oil and pulses to ensure that if our farmers grow canola or lentils, they aren’t undercut by a sudden influx of cheap imports at harvest time. In other words, if we want farmers to shift, we must de-risk those alternatives. This might mean initially guaranteeing a minimum price for certain new crops (much as India sets MSPs for many crops but with focus on a few) or at least having government or large buyers signal they will procure a certain amount. Over time, as markets develop, such support can be withdrawn, but a jump-start is needed. By broadening the crop mix, Pakistan can improve its agricultural resilience and reduce over-reliance on wheat. Crop rotation would also improve soil health (continuous wheat impoverishes soil nutrients and invites disease). There is an environmental and long-term productivity gain in diversification, which policy should articulate as a national goal.

-

Safeguard Food Security with Smart Trade and Reserves: A big fear in moving away from MSP is that Pakistan might face wheat shortages or become too reliant on imports. It’s true that if farmers drastically cut wheat acreage in response to poor prices, output could drop and the country might need to import more wheat. But imports are not inherently bad if managed smartly and if the economy can afford them. Pakistan already resorted to imports in various years (including the $1 billion spent in late 2022/early 2023 to import 3.5 MMT). The problem was the timing – importing right before a bumper crop was poor planning. In a reimagined policy, Pakistan could adopt a “critical reserve” approach: maintain an emergency buffer (maybe 1-2 MMT) either through domestic purchase or forward contracts from abroad, that can be released if domestic production falls short or prices spike wildly. But beyond that, allow normal supply to be handled by the private sector through trade. In surplus years, enable exports so farmers get better prices – currently, whenever we have a bit of surplus, the government is hesitant to allow exports for fear of domestic shortage. If we have good data and stock monitoring, limited exports can be safely done, putting a floor under domestic prices. In deficit years, enable imports in a timely manner – but here’s the catch: try to import well before the next harvest, not during or right after it. For example, if a shortfall is projected, import right after harvest season (to top up stocks) or in the off-season, rather than when farmers are about to sell new wheat. This avoids flooding the market at the wrong time. The wheat trade could also be linked to currency and foreign policy considerations – e.g., importing from Central Asian neighbors or Russia when prices are favorable through government-to-government deals can sometimes yield better terms (Pakistan did some G2G wheat import deals in recent years). The guiding principle is “food security through diversity”: some of our wheat can come via international trade when needed, just as we comfortably import other food items, and that’s fine as long as it’s affordable. But we should also not abandon the idea of strategic reserves. Rather than having the government buy 6 MMT each year and carry huge stocks (and debt), it could maintain a smaller reserve and even explore using commodity financing or storage contracts with the private sector. Modern approaches like warehouse receipt systems can let the market hold stocks with government oversight. Ultimately, Pakistan can balance being largely self-sufficient in average years with being connected to global markets in bad years. That flexibility is better than rigidly aiming for 100% self-reliance regardless of cost.

-

Identify Winners/Losers and Cushion the Transition: It’s clear that a full liberalization will not affect everyone equally. Large, efficient farmers and agribusinesses stand to manage well – they can handle price swings, store grain, hedge risk, or shift to other crops relatively easily. Many small and medium farmers, on the other hand, could face income volatility and lower returns, as seen in 2024 when market rates plunged and many farmers barely covered their costs. To prevent a surge in rural poverty or abandonment of farming, targeted support is needed. One approach is to replace price supports with direct income supports for farmers. For example, the government could expand cash transfer programs (like the Benazir Income Support Programme) specifically for small farming households, or introduce a “farm income support” payment per acre cultivated. This would put money in farmers’ pockets without distorting crop prices. Another approach is a “price loss coverage” scheme – if at harvest the average market price is below a certain benchmark (like the cost of production), the government could pay farmers the difference on, say, a fixed quantity per small farmer. This kind of safety net exists in some countries and acts as an insurance for farm income. It’s crucial that any such support be targeted – unlike MSP which went to all wheat growers big or small, these new supports should focus on smallholders who truly need cushioning. Large farms can likely cope on their own in an open market; small farms might need time and help to adjust.

-

Build Safety Nets and Support Services: In a reimagined policy, the role of the government shifts from buying wheat to empowering farmers. This means strengthening services like agricultural research, extension, and rural finance. Improved extension can teach farmers how to increase wheat yields or diversify to other crops (raising their competitiveness). Better access to credit will enable them to invest in those improvements. Moreover, establishing crop insurance or disaster insurance programs would address one of farmers’ biggest fears – a bad weather year wiping them out. Currently, crop insurance in Pakistan is negligible. The government could subsidize premiums for a simple wheat crop insurance scheme (perhaps starting in climate-vulnerable areas) so that even without MSP, farmers have protection against a bad drought or flood. Similarly, organizing farmers into cooperatives or associations can help them gain market power and scale. Cooperatives could bulk their wheat together to sell at better rates or to store until off-season when prices rise. They could also collectively invest in processing or value addition. These are the kinds of indirect supports that make a liberalized system viable and more equitable.

- Dawn. (2025, April 12). Farmers announce province-wide protests over wheat pricing. Dawn. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1903631

- Adnan, I. (2025, April 11). Farmers, PTI slate deregulation. The Express Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2539147/farmers-pti-slate-deregulation

- Hussain, A. (2024, May 3). Why are Pakistan’s wheat farmers protesting against the government? Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/5/3/why-are-pakistans-farmers-protesting-against-the-government

- Miller Magazine. (2024, July 11). Pakistan’s grain outlook. Miller Magazine. Retrieved from https://millermagazine.com/blog/pakistans-grain-outlook-5789

- Razzaq, A. (2025, April 14). Liberalizing wheat prices in Pakistan: At what cost and without safety nets? Amar Razzaq Insights. Retrieved from https://amarrazzaq.com/insights/liberalizing-wheat-prices-pakistan.html

- Vaneeta. (2024, April 25). Farmers in Pakistan’s Punjab threaten to protest: Five reasons why. Pakistan Reader. Retrieved from https://www.pakistanreader.org/view_articles.php?recordNo=758

- Haq, S. (2025, April 16). Scrapped wheat price triggers alarm. The Express Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2540113/scrapped-wheat-price-triggers-alarm

- South Asia Network TV. (2024, June 3). KP govt stops purchase of wheat from Punjab farmers. South Asia Network TV. Retrieved from https://en.sicomedia.com/2024/0603/38970.shtml

- Dawn Editorial. (2024, April 24). Farmers’ anxiety. Dawn. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1829322

- Khan, D. (2022, September 2). Smallholder agriculture — emergence of production clusters. The Express Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2374250/smallholder-agriculture-emergence-of-production-clusters

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2024). Agricultural mechanization for smallholder farmers in Pakistan: Results of a multistakeholder policy dialogue – Policy brief. FAO. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0369bd1a-11de-4d1c-9838-ae9f6eda312a/content

- Khyber Journal of Public Policy. (2024). Mechanizing the agriculture sector for higher yield, crop diversification, and precision agriculture (Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp. 118–133). Retrieved from https://nipapeshawar.gov.pk/KJPPM/PDF/CIP/P15.pdf

- Siddiqui, S. (2024, September 16). Policy missteps threaten agriculture. The Express Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2496421/policy-missteps-threaten-agriculture

- Haq, S. (2025, January 2). Farmers suffer despite bumper crops. The Express Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2519510/farmers-suffer-despite-bumper-crops

- Ahmed, A. (2025, April 21). Removal of support price increased availability of wheat: FAO. Dawn. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1905583

Finally, the government should articulate a clear long-term vision: for instance, announce that “we aim to move to an open wheat market over X years, during which we will implement A, B, C support measures for farmers and consumers.” This kind of clarity can restore some trust and allow all stakeholders to plan accordingly. The vision might include maintaining self-sufficiency in wheat except in bad crop years, encouraging crop diversification to improve farm incomes and reduce imports, and replacing general subsidies with targeted assistance. If farmers hear this and see it backed by consistent policy (not flip-flops), they will gradually adjust.

In conclusion, rethinking wheat policy does not mean abandoning Pakistan’s farmers or jeopardizing food security. It means moving from an old model to a more sustainable one: from heavy-handed price fixing to a market-guided system buttressed by smart safety nets and investments. The support price saga revealed that clinging to the old ways can create new crises, but also that abrupt change is perilous without preparation. The way forward lies in a middle path – phasing out distortionary subsidies while phasing in direct support and competitive opportunities. Pakistan can ensure that wheat remains abundant and affordable by being smarter in how we support those who grow it and how we manage what we need. In short, the country’s wheat policy needs a new equilibrium for a new era: one that lets markets work, farmers thrive with diversified incomes, and consumers access their daily roti at a fair price. With careful planning and commitment, the painful lessons of the support price saga can be turned into a catalyst for a stronger, more resilient agricultural future.