The Shift Toward Market Liberalization

Pakistan is now reconsidering one of its longest-standing agricultural policies – the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat. In early 2025, under significant fiscal strain and pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the federal government decided to stop announcing a wheat support price 1. This marks a dramatic policy shift: for decades the state procured wheat at a fixed MSP to protect farmers and stabilize consumer prices. The IMF-backed reforms aim to “deregulate” the wheat market as part of broader efforts to cut subsidies and reduce the budget deficit 2 3. The rationale is classic free-market theory – let supply and demand set prices, avoid distortionary subsidies, and ease the burden on a cash-strapped exchequer 4.

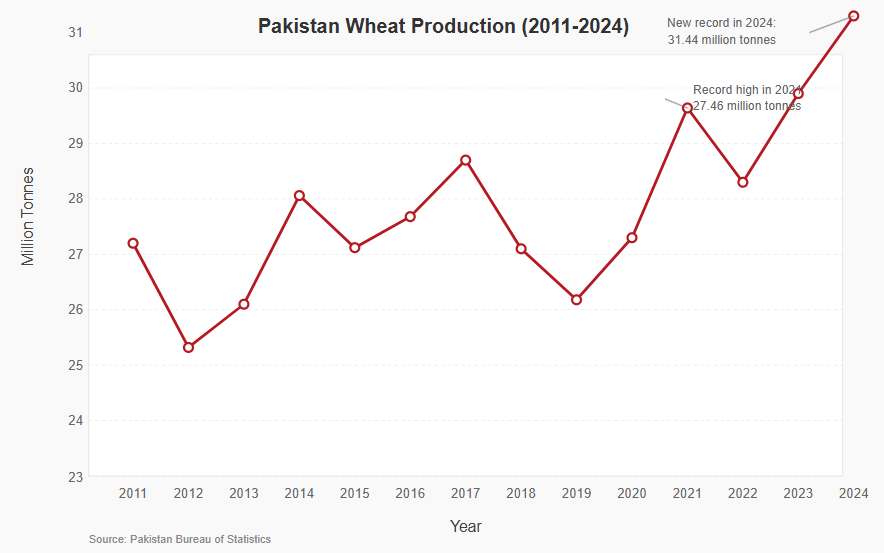

However, wheat is not just any commodity in Pakistan – it provides about 72% of average caloric intake and is integral to rural livelihoods 4. Recent experience shows the stakes. In 2022–23, heavy floods and poor procurement led to a wheat shortage and soaring flour prices, from around PKR 70/kg to PKR 400+/kg, sparking protests across cities 4. By contrast, a bumper harvest in 2024 (over 28 million tonnes of wheat 5 ) combined with large imports left markets oversupplied, causing farm-gate prices to crash well below the MSP 6. This volatility underscores a dilemma: reforms are needed, but so are safety nets. Pakistan must balance freeing the wheat market with protecting those who stand to lose the most.

Pakistan’s wheat production has fluctuated between ~24 and 28 million tonnes in recent years, reflecting climate impacts and variable yields. Good weather and more area in 2024 produced a record crop, after a flood-affected 2023 harvest.

2. The Case for Liberalization

From a fiscal and efficiency standpoint, the case for ending the wheat MSP is strong. The subsidy costs have become staggering – over Rs 300 billion per year of taxpayer money is spent on wheat procurement and related operations 7. This includes the financing of government purchases (often via bank loans) and losses from selling wheat at subsidized rates. Such expenditure is hard to sustain amid a budget crisis and mounting public debt. Indeed, fulfilling IMF bailout conditions, Pakistan agreed not only to abolish the MSP but even to consider shutting down PASSCO, the state grain agency, due to “irregularities in wheat distribution and finance” 2. By exiting the market, the government can redirect funds to pressing needs like infrastructure or debt repayment.

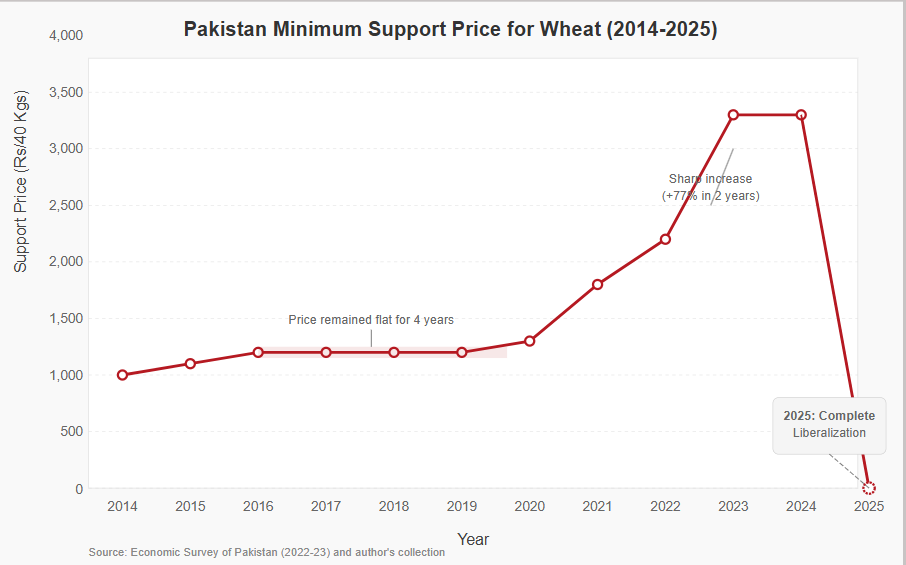

Proponents argue that MSP intervention has bred market inefficiencies. Despite its intent to help farmers, the MSP system often led to outcomes where middlemen and flour millers benefited more than growers 7. In fact, in several recent years private traders were paying farmers above the fixed support price – indicating that the government was “failing to protect farmers’ interests” 7. At the same time, when the state did procure at high MSP, it drove up flour costs for consumers, who form the majority. One analysis noted that raising the MSP from Rs 2,200 to Rs 3,900 (77% jump) could increase an average Pakistani’s yearly wheat expenditure by around Rs 5,000 8. In 2022–23, the MSP hike to Rs 3,900/40kg far exceeded production cost increases, contributing to record profits for hoarders while burdening consumers with inflation 8. In short, the MSP became fiscally costly and regressive, taxing the urban poor to subsidize (often richer) farmers 8.

Liberalization would also remove the distortions that have plagued Pakistan’s wheat sector: periodic gluts and shortages. Analysts at PIDE have long argued that heavy government involvement prevented a robust market from developing 9. The result has been a cycle of “excesses and shortages” – some years, the government over-buys and ends up with rotting stocks; other years, it under-buys and a shortage ensues 10. By withdrawing from price-setting and procurement, the government could allow more competition and investment in storage, reduce corruption and “rent-seeking” in grain operations, and rely on imports or exports to balance the market 11. Notably, Pakistan has often imported wheat even when it had carryover stocks, pointing to mismanagement 7. A true free market might trade more efficiently: buying grain when and where it’s cheapest (domestically or abroad) and ensuring steady supplies without massive subsidies. In theory, with open trade the international market can fill supply gaps quickly, minimizing the risk of shortages 12.

Finally, liberalization is being encouraged by international lenders not just as a cost-cutting measure but as a structural reform to boost agriculture. The World Bank notes Pakistan’s wheat yields remain low, and distorted incentives have hindered investment in the sector. Removing MSP could encourage diversification to higher-value crops in areas where wheat is less competitive. It might also spur improvements in quality – currently, government procurement cares only about quantity, but a market-driven system would reward better grain quality and grading. Over time, a leaner public role (limited to maintaining emergency reserves) and a bigger private role could modernize the supply chain. For these reasons, the federal food security ministry has signaled “unwavering resolve” to implement wheat market reforms in true spirit 7. The trajectory of the MSP itself tells the story: it was largely flat for years and then shot up during recent crises, before this abrupt removal. Figure 2 illustrates this trend and the breaking point reached.

In sum, the argument for liberalization is that the wheat MSP had become financially unsustainable and economically inefficient. The government’s heavy hand may have done more harm than good in recent years – hurting consumers, wasting funds, and failing to truly uplift small farmers. Freeing the market, supporters contend, will reduce fiscal bleeding and unleash market forces to the benefit of overall efficiency.

Pakistan’s official Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat was kept around Rs 1,200–1,300 per 40kg through the mid-2010s, then raised modestly to Rs 1,400 in 2019-20. Since 2020, steep hikes took it to Rs 2,200 and then Rs 3,900 by 2023. The MSP was abolished for 2025 under an IMF agreement, dropping support to zero.

3. Who Bears the Risk?

The flip side of ending MSP is who shoulders the risks of price swings and low prices. Under a liberalized regime, farmers are exposed to the full volatility of the market. This impact will not be uniform; it will vary across different farming groups and regions:

-

Smallholders (subsistence farmers) – paradoxically, the smallest farmers may be somewhat insulated from price collapses, because they sell little surplus. Many have tiny plots and consume a large portion of their wheat harvest at home. Studies show Pakistani small farmers typically eat or save over half their output (for seed and feed), sharing only a bit with markets 7. Thus, when prices fell in 2024, some subsistence farmers were hurt less than medium-scale farmers who had more wheat to sell 7. However, smallholders are still very vulnerable overall – they have thin margins and any loss of income can be devastating. Most live near or below the poverty line, and many are land-poor or landless sharecroppers who did not directly benefit from MSP anyway 9. For them, the bigger risk is if wheat farming becomes unviable and they have no alternative livelihood. Landless laborers, in particular, could suffer if farm incomes drop – lower profits mean less ability to hire labor at harvest, squeezing rural employment and wages.

-

Medium-scale farmers – these are often the backbone of marketable wheat surplus. They will bear the brunt of MSP removal in terms of income loss. For example, when Punjab halved its procurement in 2024, market rates plunged to ~Rs 3,000/40kg (well below the Rs 3,900 MSP) in major producing districts 6. Farmers with larger surpluses saw their earnings collapse to barely cover production costs 7. Many medium farmers had invested in higher inputs (fertilizer, etc.) expecting MSP, and were caught off guard by the policy U-turn 7. The shock of low prices can ripple into the next season: farmers use the previous year’s price signal to decide how much wheat to plant. Unfavorable prices now may lead these farmers to reduce wheat acreage next year, potentially undermining national output 7.

-

Large farmers (agro-industrial) – well-capitalized farmers with hundreds of acres can better withstand volatility. They often have on-farm storage, access to credit, and political influence. In fact, critics of MSP argued it mainly benefited larger landowners who could produce surpluses and secure government procurement, whereas small farmers sold to village dealers out of urgency 8. Large farmers might manage without MSP by hedging (storing grain until prices improve, or diversifying crops). However, they too face risk: if wheat becomes consistently less profitable, even big players might shift to other crops (sugarcane, maize, etc.), which could reduce national wheat supply. Regionally, a lot of big wheat producers are in Punjab, which could see structural changes in its crop mix.

-

Rain-fed (barani) wheat farmers – about 12% of Pakistan’s wheat comes from rain-fed areas, which include parts of northern Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan. These farmers already contend with yield variability and climate risk. Without a price floor, a good rain-fed harvest could flood local markets and crash prices, while a drought year yields nothing. The MSP at least gave them a guaranteed buyer in good years. Now, barani farmers fear being at the “mercy of exploitative traders” who might offer rock-bottom rates in harvest glut periods 13.

-

Province-level differences – Punjab grows the majority of Pakistan’s wheat, and for years its farmers were the main suppliers to the public procurement. Sindh, while a smaller producer, also set its own support price (often matching Punjab’s). Now both provinces have to step back from price-setting 14 13. The concern in Sindh and Balochistan is acute: farmer associations like the Sindh Abadgar Board warn that “immense financial losses” will hit growers and even discourage wheat cultivation in these provinces 13. They note that input costs (like fertilizer, diesel for pumps) are very high – if output prices are left low, farming becomes unsustainable 13.

In essence, the risk of liberalization is transferred to farmers, especially those without buffers. The MSP was a safety net for growers; its removal without alternatives means income volatility and potential losses. When prices collapse, small and medium farmers could be pushed into debt or poverty. Landless farm workers indirectly suffer when farm incomes fall or crop area shrinks. And if enough farmers respond by reducing wheat sowing, the country could face a supply crunch later, forcing expensive imports – a kind of whiplash effect. This is why farmer unions across Pakistan have vehemently opposed the MSP withdrawal, calling it an “anti-farmer agenda” 15.

4. What Safety Nets Exist – And What’s Missing?

If Pakistan is to liberalize wheat prices responsibly, robust social safety nets and support programs must be in place. Currently, however, the existing schemes are limited and not tailored to price shocks in agriculture:

-

Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) – This is Pakistan’s flagship social protection program, providing cash transfers to the poorest households (around 5–8 million families). While BISP is crucial for poverty relief, it is not crop-specific. It gives a flat stipend (quarterly payments) mainly to poor women, regardless of their occupation 16. A poor farming family may receive BISP, but the amount is modest – not nearly enough to offset a bad harvest or low crop price. Furthermore, many lower-middle-income farmers (who are above the poverty threshold but still vulnerable) do not qualify for BISP. Thus, as a cushion for MSP removal, BISP is inadequate. It was never designed to compensate income loss from policy reform; rather it prevents destitution. Without an expansion or special window for affected farmers, BISP leaves a coverage gap for those “newly poor” or hurting from price declines.

-

Kissan Card and input subsidies – Provincial governments, notably Punjab, have introduced “Kissan Card” schemes to deliver subsidies on farm inputs (seeds, fertilizer, machinery). For example, Punjab’s Kisan Card program offers subsidies on tractors (up to Rs 1 million on a tractor purchase) and provides access to cheaper farm equipment through machinery pools 17. Balochistan launched a similar Benazir Kisan Card to help small farmers buy fertilizer and seed 18. These initiatives signal recognition that farmers need support – but they are limited in scope and scale. Subsidizing a tractor or some fertilizer is helpful, yet it only reaches those who apply and qualify (often larger or registered farmers). Many small farmers are not even aware of these programs or lack the paperwork to benefit. Moreover, these schemes don’t directly address price risk or income support – they reduce costs somewhat, but if wheat prices fall by, say, 20%, a one-time subsidy on a bag of fertilizer will not save the farmer’s season. The Kissan Card also faced teething issues (e.g. shifting to digital applications in Punjab caused confusion 6). Thus, while valuable, these are no substitute for a safety net against market volatility.

-

Crop insurance – One glaring missing piece is crop insurance or price insurance. Pakistan has virtually no widespread crop insurance program. A few pilot projects of weather-index insurance have been tested (for instance, covering crop or livestock losses in parts of Punjab and Sindh), but there is no national scheme shielding farmers from either weather disasters or price crashes. This is a critical gap. In a liberalized system, farmers could in theory use futures contracts or private insurance to hedge prices, but such financial instruments are undeveloped in Pakistan’s agriculture. The typical farmer has no access to insurance and instead relies on informal coping (loans from shopkeepers, etc.) when things go wrong. The absence of crop insurance means farmers carry all the risk of a bad season or market glut.

-

Price stabilization mechanisms – Previously, the government had tools to stabilize prices: releasing government wheat stocks to cool down flour prices, or banning exports in a shortage, or conversely importing to curb spikes. With deregulation, officials are pledging not to interfere in movements or trade 19. However, there is no alternative mechanism (like a futures market or commodity exchange) that farmers can count on to lock in prices. The government does maintain some strategic grain reserves, but if PASSCO is curtailed, even that capacity might shrink 2. In 2024, we saw the government reluctant to intervene when prices fell – it cited technical excuses like high moisture grain to avoid buying from farmers 6. This left farmers without a floor. The lack of a formal price stabilization fund or emergency procurement plan is a major omission.

-

Rural services and credit – Beyond direct safety nets, indirect support like agricultural extension, marketing infrastructure, and rural credit can help farmers be resilient. Unfortunately, these services in Pakistan are underdeveloped. Storage is a good example: small farmers often sell right after harvest (when prices are lowest) because they lack on-farm storage or need immediate cash. If warehouse receipt systems or community granaries were available, they could store grain and sell later at better prices. But investment in rural storage and cold chains has been minimal. Likewise, extension services that could help farmers cut costs (via better farming practices) or diversify crops have weakened over time. Access to affordable credit is also limited – farmers often borrow from informal lenders at high interest, which can trap them in debt if crop returns dwindle. So, the supporting ecosystem that would make liberalization workable (credit, storage, info services) is largely missing or insufficient in Pakistan.

In summary, the current social protection landscape has no dedicated safety net for farmers facing price risk. General poverty programs (BISP) cover only the very poor and provide small relief. Targeted farmer programs focus on inputs, not incomes, and reach a subset of farmers. Key instruments like crop insurance or price guarantees are absent. Without filling these gaps, removing MSP is akin to “pulling the rug out” from under farmers. The government itself acknowledged that intervention was meant to protect producers from price fluctuations 19 – if that function is removed, something else must replace it. As of now, that something is largely hypothetical. This deficiency heightens the danger that liberalization will worsen rural poverty and food insecurity before any gains materialize.

5. Global Lessons: Liberalization with Safety Nets

Pakistan is not the first country to wrestle with the question of farm price supports and how to reform them. International experiences offer cautionary tales and potential models:

-

India – India’s example illustrates farmers’ deep reliance on support prices. India maintains MSPs for many crops (including wheat and rice) and a massive public procurement system. In 2020, the Indian government attempted to liberalize agriculture through new laws that encouraged private trade and limited the state’s role. Farmers feared these laws would dismantle the MSP guarantee, leaving them at the mercy of big agribusiness 20. The result was one of the largest protests in history: tens of thousands of farmers camped around Delhi for over a year. They demanded a legal guarantee for MSP and ultimately forced the repeal of the reforms 21. The lesson from India is that even if market reforms have merit, implementing them without the trust of farmers and without credible assurances of protection will provoke fierce resistance. India ended up retaining MSPs and is now deliberating how to reform procurement more gradually. For Pakistan, the takeaway is clear: abrupt removal of price support is politically and socially perilous. Farmers need confidence that they won’t be abandoned to volatile markets. Notably, India’s farmers argued that without MSP, corporate buyers could “control prices” and erode their livelihood 21.

-

Mexico – In the 1990s, Mexico underwent a major liberalization of its staple grain market under NAFTA. The government eliminated its system of guaranteed maize prices (previously enforced by a state agency, CONASUPO). Recognizing that this could hurt small maize farmers, Mexico introduced a direct cash transfer program called PROCAMPO as compensation 22. Under PROCAMPO, farmers received cash payments per hectare of land cultivated, regardless of market price, for a transitional period. In parallel, Mexico launched conditional cash transfers (Progresa/Oportunidades) aimed at poor rural households 23. The outcome was mixed: large commercial farms thrived, while many small farmers planted for consumption. The cash transfers alleviated extreme poverty and improved food security 23. The key insight is that Mexico did not liberalize without cushioning the blow.

-

Kenya – Kenya historically did not have nationwide grain price supports, but in recent decades it developed innovative safety nets for rural communities. One example is the Hunger Safety Net Programme (HSNP) in Kenya’s arid north. This program provides regular cash transfers to poor households and scalable payouts during droughts 24. In addition, Kenya piloted index-based insurance schemes for farmers and pastoralists. For instance, a drought-index insurance triggers payouts when rainfall drops 25. Studies show that with subsidies or flexible payment schedules, farmers readily embraced it and were more resilient 25.

-

Ethiopia – A case often cited for cushioning agricultural risks is Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP). It provides food or cash-for-work to rural poor during lean seasons 26. It is flexible to scale up in drought years. 27. The Ethiopia example underscores that liberalized markets must be paired with robust safety nets to protect the poor.

Each country’s context differs, but the overarching theme is “reform with responsibility.” Countries that managed to reform agricultural pricing did so gradually and with parallel measures to secure farmer livelihoods. They often retained some public role (e.g., buffer stocks, emergency buying) and introduced compensatory programs (direct payments, insurance, or employment guarantees). Pakistan can draw on these lessons: simply copying a free-market approach without the accompanying safety architecture is likely to fail. Successful reformers invested heavily in institutions and social programs during the transition.

6. What Can Be Done Now?

1. Direct Cash Support to Farmers – Targeted and Conditional: Instead of spending billions on inefficient procurement, the government can allocate a portion of those funds to direct cash transfers for wheat growers. For example, a “Wheat Income Support” could be given to farmers owning, say, under 5 hectares who cultivate wheat, with the amount calibrated to their acreage or output. This would act as a de facto safety net payment when market prices are low, but without distorting market prices because the government isn’t buying or selling wheat – it’s simply supplementing incomes. The support could be seasonal (during harvest time) and conditional on proven wheat cultivation. Modern tools like the Kissan Card and e-vouchers can help target these payments directly to farmers’ bank accounts, reducing leakage. This approach echoes Mexico’s PROCAMPO and could be funded by savings from not having to purchase and store wheat. It would ensure small farmers get something in their hand even if prices crash.

2. Gradual and Differentiated Implementation: Rather than a nationwide abrupt removal of MSP, Pakistan could phase the reform by region or by scale of farmer. For instance, the government might continue a form of minimum price support in the most vulnerable regions for a few more years, while completely freeing the market in more productive areas. This graduated withdrawal allows time for adaptation. Alternatively, MSP could be retained but only for a limited quantity per small farmer. Punjab’s mis-timed exit in 2024 taught a lesson: doing it “cold turkey” in a year when stocks were high crushed prices 76.

3. Regulated and Transparent Grain Markets: Liberalization doesn’t mean a laissez-faire free-for-all. The government should play a regulatory role to ensure markets remain fair. One priority is to prevent cartelization by millers or traders. In 2024, millers allegedly formed a cartel and bought grain at extremely low prices from farmers 7. To counter this, competition law must be enforced in agricultural markets. The government can facilitate electronic commodity exchanges or auction markets. Digital platforms 3 could allow real-time price discovery and reduce reliance on middlemen. Public-private partnerships could support warehousing and collateral financing. The state’s role shifts from buyer to market referee and facilitator.

4. Strengthen Safety Nets and Insurance Mechanisms: As discussed, current safety nets are insufficient. The government should expand programs like BISP in rural areas. It could also consider a “Price Loss Coverage” scheme: if average harvest-time market price falls below cost, the government pays the difference. This model is used elsewhere. Pakistan should also scale up crop insurance. A weather-index or area-yield policy could be subsidized by the government and integrated with social protection. Kenya’s model shows this is possible 25. The goal is to protect farmers from catastrophic loss.

5. Early Warning Systems and Adaptive Actions: Pakistan’s meteorological and agricultural departments should set up early warning systems. If a drought or bumper crop is forecast, the government can pre-emptively import/export or intervene. An Agricultural Market Information System that tracks projected supply/demand would help. The government should also stabilize extreme peaks or troughs through timely actions. A small strategic grain reserve should be kept to prevent food inflation or panic. Climate investments like drought-tolerant wheat and water systems are essential. These tools together replace MSP with smart, responsive policy.

In implementing these steps, communication and inclusion are vital. Farmers must be at the table during policy design – through their unions and associations – so that solutions are practical and acceptable. If farmers see that the government is replacing MSP with other meaningful support, they are more likely to cooperate. A combination of direct support, smart regulation, and risk management tools can steer Pakistan toward a market-oriented system without crushing the vulnerable.

7. Reform Yes, But With Responsibility

Pakistan stands at a crossroads in its wheat policy. On one hand, the need for reform is evident – the status quo of ever-rising support prices, costly procurement, and market distortions is no longer tenable financially or economically. Moving toward a market-driven wheat sector could improve efficiency, encourage innovation, and relieve the fiscal burden. The decision to liberalize wheat prices is therefore not without merit. However, reform must be pursued with a sense of responsibility and realism. Stripping away price supports without adequate safety nets can do more harm than good, at least in the short to medium term.

If poorly managed, the end of MSP could exacerbate rural poverty, increase inequality among farmers, and even undermine food security (if production falls due to farmers exiting wheat). The social and political fallout could be severe – discontent in the countryside, farm protests, and pressure to revert the policy (as India experienced). Thus, the question “Can Pakistan afford to liberalize wheat prices without safety nets?” might be answered by another question: can Pakistan afford the potential consequences of doing so? The prudent course is not to backtrack on reform, but to couple reform with robust protections.

A balanced path entails maintaining the commitment to market liberalization – letting prices adjust to true supply/demand, fostering private sector solutions – while actively shielding those most at risk from volatility. This means significantly strengthening social protection for farmers, whether through cash transfers, crop insurance, or other innovative programs. It means phasing in changes rather than springing them overnight, giving farmers time and tools to adjust their cropping patterns and cost structures. And it means the state shifting its role from market participant to market facilitator – preventing abuse, ensuring information flow, and being ready to step in during genuine crises.

Ultimately, reform of the wheat sector is not about choosing markets or safety nets; it must be about markets and safety nets. Pakistan’s policymakers should recall that the original purpose of MSP was to serve as a safety net itself. If that net is being removed due to fiscal and efficiency imperatives, an alternative net must catch those who fall. Liberalization can unlock growth, but inclusivity demands that growth does not leave the small farmer behind. By learning from global experiences and heeding the voices of its own farmers, Pakistan can pursue wheat market reforms that are fiscally sensible and socially responsible. The path forward should ensure that economic rationalization does not come at the cost of human welfare. In the end, the measure of success will be a wheat sector that is both more efficient and more resilient – where farmers compete and prosper in open markets, supported by the assurance that they will not be ruined by forces beyond their control. Reform, yes – but with empathy, gradualism, and unwavering commitment to protect the vulnerable. That is the only affordable way to truly transform Pakistan’s wheat economy for the better.