Introduction

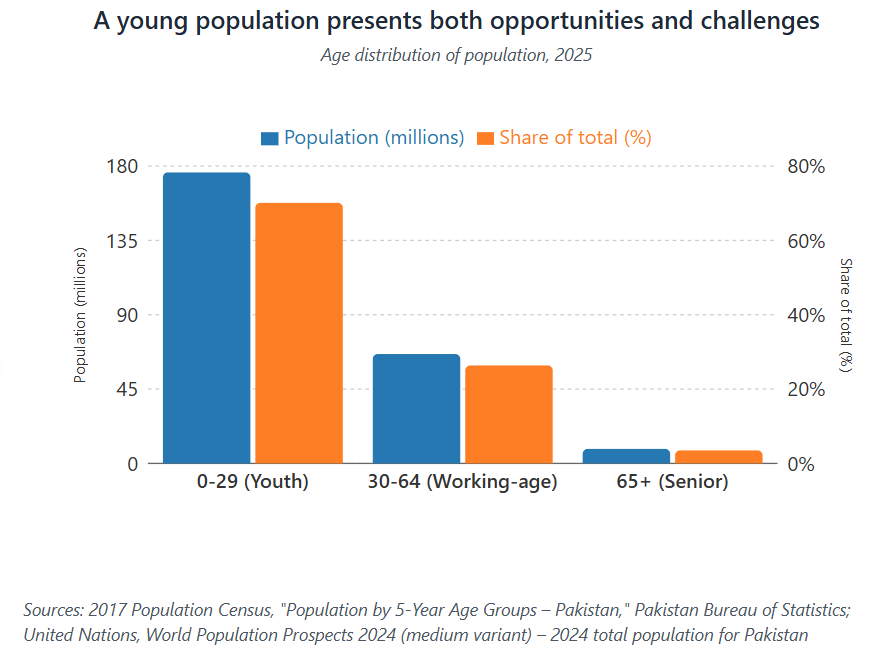

Agriculture remains the backbone of Pakistan’s economy and society. It contributes around 23% of GDP and employs about 37% of the labor force, while roughly 60–70% of the population depends on farming for livelihood either directly or indirectly. Beyond economics, the agricultural way of life anchors rural communities and food security. Yet Pakistan faces a pivotal demographic tension: a massive youth cohort on one hand – roughly 64% of Pakistanis are under 30 – and an agricultural sector increasingly shunned by this younger generation on the other. Rural youth have been migrating in large numbers, whether to cities or abroad, in search of better opportunities. Villages report shortages of farm labor even as educated young Pakistanis struggle with underemployment – a glaring paradox noted in recent studies. In short, fewer young people see a future in farming, despite limited jobs elsewhere. This commentary examines the causes and consequences of this youth exodus from agriculture and explores how Pakistan can re-engage its educated youth to revitalize the farming sector. We begin by reviewing the “vital signs” of Pakistani agriculture – its workforce, land use and productivity – to understand what’s at stake.

Pakistan’s 2024 population shows a strong youth bulge, with over 70% of people under the age of 30, highlighting the urgency of engaging this cohort in productive sectors like agriculture.

Agriculture’s Vital Signs

An Aging Farm Workforce: Pakistan’s agricultural labor force is greying. The share of employment in agriculture has declined (from 39.2% in 2018–19 to 37.4% in 2020–21), and most of those remaining are older workers. One comparative study found “55% of farmers from Pakistan have age more than 50 years”. By contrast, youth under 25 form a much smaller fraction of farmers today. This aging trend reflects both younger workers leaving and the traditional inheritance pattern where farm ownership and decision-making rest with older family members. The gender breakdown also highlights who is staying behind: nearly 68% of employed women work in agriculture (often as unpaid family labor), compared to only 28% of employed men. In sum, the countryside is increasingly populated by an older, predominantly female agricultural workforce, while young men – and many young women – pursue opportunities outside farming. This raises concerns about who will carry Pakistani agriculture forward in the coming decades.

Land Use and Underutilization: Pakistan is endowed with extensive agricultural land, but not all of it is being utilized efficiently. Out of ~79.6 million hectares of total land, about 22.5 million hectares are currently cultivated (sown in the last year or kept fallow). Thanks to the Indus irrigation system, much land is double-cropped; the total cropped area is around 24 million hectares, implying a national cropping intensity of roughly 150%. This means many farms plant two crops per year (e.g. wheat in winter and rice or cotton in summer). Cropping intensity has gradually increased (up from ~145% a decade ago) as farmers strive to maximize output from limited land. However, a significant portion of arable land remains under-utilized. Approximately 8.2 million hectares are classified as “culturable waste” – land that is capable of cultivation but lay idle for at least the past two years. Another ~6.8 million hectares are “current fallow,” land that was cropped in recent past but not this year. These figures suggest that nearly half of Pakistan’s potential farmland is not consistently cropped. Water scarcity, land degradation, and socio-economic factors (like absent landowners or lack of labor) contribute to this underutilization. Engaging energetic young farmers could be key to bringing some of this idle land back into production.

Output and Productivity Trends: The performance of Pakistan’s agriculture has been mixed. On the one hand, the sector still accounts for about 22–24% of GDP and has seen occasional spurts of robust growth (e.g. 3.5% in 2020–21, and an estimated 6.3% in 2023–24 after a good harvest year). Major crops – wheat, rice, maize, cotton, sugarcane – are grown in abundance, and Pakistan is among the world’s top producers of commodities like cotton, milk and rice. On the other hand, yield levels have improved only slowly and inconsistently, signalling stagnating productivity. For example, wheat yields hovered around 2.8 tons per hectare in 2010–11 and crept up to only about 3.0 tons/ha by 2020–21. Rice yields (paddy) averaged ~2.0 t/ha in 2010 and rose to ~2.9 t/ha by 2020 – better progress, yet still low compared to global standards. Sugarcane yields increased from ~56 to ~70 t/ha over the decade, reflecting some gains, while maize saw a jump (thanks to hybrid corn adoption) from ~3.8 to ~6.3 t/ha. Troublingly, cotton yields declined – from ~725 kg/ha a decade ago to barely ~578 kg/ha in 2020 – due to pest and disease pressures and lagging seed technology. These trends underscore that Pakistan’s yield growth has lagged behind its peers, and in some cases regressed. Agriculture’s share of GDP has fallen to about 22–23%, even though it still employs 37% of workers, implying low productivity per worker. (In fact, agriculture’s GDP share is disproportionately low relative to its workforce share, indicating lower value-added and incomes in farming versus other sectors.) Without new blood injecting modern practices, there is a risk that output will plateau or fall behind population needs. Notably, within agriculture, the livestock sub-sector now contributes 62% of value (14% of GDP) – primarily dairy and meat – whereas crops (important + other) are only ~7.4% of GDP combined. Crop yields stagnating, while demand for food rises, is a recipe for food security challenges if not addressed.

Provincial Patterns and Irrigation vs. Rainfed: Pakistan’s agriculture is diverse across its provinces and agro-ecological zones. The bulk of cropped area and production lies in the fertile, irrigated plains of Punjab and Sindh, which benefit from the Indus River irrigation system. Punjab alone typically produces the majority of wheat and cotton, and a large share of sugarcane and maize, while Sindh dominates in rice and also grows cotton, wheat and sugarcane. In the smaller provinces, agriculture is relatively smaller-scale: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) has predominantly smallholders growing wheat, maize, tobacco and orchard crops (and is a major livestock producer), often on rain-fed plots or using limited irrigation from rivers and tube-wells. Balochistan, being arid and sparsely populated, contributes only a few percent of national crop output, focusing on fruits (apples, dates), vegetables and livestock in oasis-like pockets (using karezes, tube-wells and limited canal irrigation). These regional differences are reflected in land utilization. Nationally, about 82% of the cultivated land is irrigated and 18% rain-fed. In Punjab and Sindh, irrigation (canals supplemented by tube-wells) is pervasive – millions of hectares are watered by the Indus basin canal network and groundwater pumps, enabling multiple cropping and higher yields. By contrast, many farms in KPK’s uplands and Balochistan rely on rainfall or sporadic water sources, limiting them to a single crop per year and lower productivity. For example, wheat yields in rain-fed northern Punjab/KPK can be less than half of those in irrigated Punjab. Such disparities mean that rural youth from rain-fed regions often see fewer prospects in farming than those from canal-irrigated districts. The reported cultivable land that remains unused is also largely in these marginal areas. Bringing modern irrigation and technology to rain-fed zones (e.g. through small dams, solar pumps, drip irrigation) could open new opportunities that might encourage youth to engage in agriculture locally instead of migrating out.

Overall, the “vital signs” of Pakistani agriculture send a mixed message. The sector is undeniably vital – supporting tens of millions of livelihoods – but it is also showing signs of strain: an aging, shrinking workforce; inefficient land use with stagnating yields in key staples; and regional pockets of underproductivity especially in rain-fed areas. These trends form the backdrop for the youth exodus from farming. Understanding why rural youth are leaving (and why that trend is problematic) is the next step in formulating solutions.

The Youth Exodus

Rural-to-Urban Migration: Pakistan has been urbanizing rapidly, fueled in large part by migration of rural youth to cities. In 1998, about 32% of Pakistan’s population lived in urban areas; as of 2023, nearly 39% is urban. Big cities like Karachi (now over 16 million people) and Lahore (over 11 million) have swelled with newcomers from the countryside. Young people form a substantial portion of these migrants, drawn by the promise of jobs, education and a modern lifestyle. Many rural families see sending a son or daughter to the city as a pathway to upward mobility. Common destinations include not only the megacities, but also emerging urban centers and industrial towns (Faisalabad, Islamabad/Rawalpindi, Peshawar, Quetta, etc.). The drivers are both “push” and “pull”: villages push youth out due to limited local opportunities (and the lures of city glamour), while cities pull them in with perceived prospects of employment, higher education, and social mobility. By the late 2010s, net rural out-migration was evident across much of Pakistan except a few remote regions. As one case study notes, “unlike the rest of Pakistan, where rural labour is migrating to cities, rural youth from Kurram (a tribal district) are increasingly migrating outside of Pakistan” – implying that in most places the norm is indeed rural-to-urban migration. This flow of youth has contributed to labor shortages back on the farms (more on that later), but for the individuals involved, the move is often seen as necessary. Youth with some education often prefer even informal urban work (e.g. in transport, retail, offices, or as gig workers) to toiling in fields. Young rural women may migrate for marriage or to work in city factories (though female migration is less documented). Urban migration isn’t always to major cities – sometimes it’s from villages to nearby towns or secondary cities within the same province. But the cumulative effect is clear: a “brain and brawn drain” of the countryside, as villages lose their youngest, most educated members. A 2018 UNDP survey found that youth in rural Pakistan overwhelmingly aspired to non-farm occupations, and many saw agriculture as a last resort unless it could be made more profitable and respectable. These aspirations, combined with the stark rural-urban gap in services (schools, internet, entertainment), propel the steady exodus.

Emigration Abroad from Rural Areas: In addition to internal migration, large numbers of young Pakistanis from rural backgrounds have sought opportunities abroad. Overseas migration – particularly to the Middle East – has been a major outlet for rural youth unemployment since the 1970s. This trend hit a record high recently. According to official data, 765,000 Pakistanis left for work abroad in 2022 – nearly triple the number in 2021. The vast majority are young men, many of them from rural or small-town backgrounds. Over 736,000 (96%) went to Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman and Qatar, typically on labor contracts in construction, driving, manual labor, or low-skill service jobs. The “push” factors are familiar: lack of decent-paying jobs at home, and family pressure to earn. Rural districts in Punjab and KPK are among the top sources of emigrants. Indeed, in 2022, “more than half of those leaving the country were from Punjab” (424,000 people), followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (206,000, plus 38k from the merged tribal districts). Only 54,000 were from Sindh and 7,000 from Balochistan, reflecting that Punjab and KPK’s rural heartlands supply the bulk of migrant labor. This exodus includes not just unskilled workers but also educated youth: in 2022, 92,000 emigrants were highly educated (doctors, engineers, IT experts), and notably 2,600 were agricultural experts – suggesting even some with agri degrees or skills chose foreign jobs. While international migration can benefit rural families through remittances, it physically removes young manpower and talent from local agriculture. Many villages in northern Punjab or KPK have a “youth gap,” where most able-bodied young men are abroad in Dubai or Riyadh, and only children and the elderly tend the fields (often with sharecroppers or hired help). Remittances have kept those farms going in some cases, but if migration continues unabated, fewer youths see a future on ancestral lands. Moreover, the aspiration to migrate has become ubiquitous – surveys show a high proportion of Pakistani youth (rural and urban) desire to go abroad if given the chance, due to economic frustrations at home. The result is a culture where farming is seen as a temporary activity until one can “escape” overseas. Areas like Kurram, as mentioned, are extreme cases where conflict and poverty drive youths directly abroad rather than to Pakistani cities.

Youth and the Urban Job Market: Paradoxically, even as rural youth flock to cities, many do not find the prosperity they seek – at least not immediately. Youth unemployment in Pakistan is quite high. The latest Labor Force Survey showed the highest unemployment rate is among ages 15–24, at 11.1% (compared to the overall 6.3% jobless rate). The next age bracket (25–34) also had above-average unemployment at 7.3%. This means hundreds of thousands of young people in cities are unable to secure jobs despite actively seeking work. Many end up underemployed in the informal sector – e.g. working gig jobs, day labor, or not fully utilizing their education. A common scenario is the son of a farmer gets a bachelor’s degree and moves to the city, but then struggles to find a stable salaried job; he may drive a ride-share taxi or work at a store while applying for better jobs. Such underemployment often pays little more (or even less) than what a diligent farmer could earn back home. Yet, returning to farm is seen as a loss of status, so many persist in urban areas hoping for a break. The urban economy, plagued by slow growth in recent years (GDP growth was just 0.3% in 2023), has not generated enough jobs to absorb the “youth bulge.” Every year an estimated 1.5–2 million young Pakistanis enter the labor force, many of them from rural areas, and formal job creation has fallen far short of this in the 2020s. This context is important: the broader economy’s limited capacity to employ youth is the backdrop of the farming exodus. It implies that redirecting some youth energy back to agriculture is not only about benefiting farming – it’s also one of the few viable ways to productively employ large numbers of young Pakistanis.

In summary, the youth exodus from agriculture is driven by powerful forces: migration to cities for perceived opportunity, migration abroad for higher wages, and an overall preference for non-farm careers among the younger generation. The data paints a clear picture of rural depopulation by youth. Yet, this trend is not sustainable for Pakistan’s food security and rural development – nor even for the youth themselves, many of whom end up jobless or in precarious work. To craft solutions, we must unpack why young people are disconnecting from farming, and also identify what might draw them back. That is the focus of the next section.

Understanding the Disconnect

Why are so many Pakistani youths uninterested in farming, and could anything change their minds? The reasons are multi-fold, rooted in economic “push” factors that drive youth away from agriculture and social/structural factors that diminish farming’s appeal. At the same time, there are potential “pull” factors that could entice some youths back – if certain conditions are met. We explore both sides:

Push Factors – Why Youth Leave Farming

- Low Income and Uncertain Returns: Perhaps the biggest push factor is the perception (often accurate) that farming doesn’t pay well. Small farmers face highly variable incomes dependent on the weather, pests, and market prices. A single bad crop or price crash can wipe out a year’s earnings. Many rural families remain near the poverty line. As one assessment succinctly noted, “Poor crop yields, unreliable farming income, and negative perceptions of farming drive young people to seek jobs and opportunities in urban areas”. Indeed, despite all the labor they put in, farmers often get low returns – e.g. government support prices for wheat or milk translate to very modest earnings for producers. Pakistan’s agriculture sector is marked by low productivity: it employs 37% of workers but generates only ~23% of GDP, meaning output (and by extension income) per worker is much lower than in industry or services. It’s no surprise that a youth with some education would rather take a shot at a city job that might pay a steady salary than toil on a farm yielding uncertain profit. Many rural parents themselves push their children away from farming towards “better” jobs in offices or abroad, hoping to escape the cycle of subsistence agriculture. In short, the economic opportunity cost of staying in farming is seen as too high by many young people.

- Social Status and “Uncool” Image: Farming has acquired a social stigma among some educated youth. It is often seen as a traditional, backward occupation – something one does only if they couldn’t make it in a more “modern” career. Urban lifestyles and jobs carry a certain prestige; by contrast, a villager working in fields may be derogatorily labeled as a “paindoo” (peasant/hick) in local slang. This is not just anecdotal – it’s been observed in various countries and is increasingly true in Pakistan. The IFAD’s Rural Development Report noted that rural youth view farming as ‘uncool’ and prefer urban employment. Unlike their grandparents who took pride in tilling their own land, today’s rural adolescents often aspire to wear office clothes, use computers, and have an air-conditioned workplace. Farming, being physically demanding and dependent on nature, doesn’t fit that ideal. Also, decades of public policy neglect and media portrayal have contributed to farming being seen as a “last resort” job. There is a sense that “a farmer is born, not made” – i.e. educated youth rarely choose farming as a career if they have any other option. Even language reflects this: calling someone a “kissan” (farmer) can be a put-down among youth. These negative perceptions are self-reinforcing: the more bright minds leave farming, the more it is seen as only for the old and uneducated, which then further disincentivizes educated youth from engaging. Changing this mindset is a major challenge.

- Land Constraints – Access and Inheritance: One very practical barrier is access to land. Most rural youth do not own land in their own right. Land ownership in Pakistan is typically in the hands of the older generation (parents or grandparents). Upon the owner’s death, land gets subdivided among heirs, often resulting in fragmentation into plots too small for efficient farming. Over time, average farm size has shrunk dramatically – from about 5.3 hectares in 1972 to only 2.6 hectares by 2010. In 2010, 65% of all farms were under 2 hectares (5 acres), and this share was rising. Traditional inheritance practices mean each generation further divides the land. Many young people from farming families therefore either a) have no land (if their family are landless laborers/tenants), or b) will inherit only a small piece shared with siblings. A 25-year-old might be working on his father’s farm, but he knows he won’t have full decision-making power or ownership until much later in life (if at all). This lack of ownership or control reduces motivation. Moreover, land tenancy laws can be insecure – a young sharecropper or tenant might be dissuaded from investing in improvements if he could be evicted by the landlord. Landlessness is high in rural Pakistan, though exact figures vary by region (in some districts over half of rural households own no land). Such youths have essentially no entry point into farming except as wage laborers – naturally they prefer to seek urban jobs rather than remain a farmhand. Even those with family land face the fragmentation issue: farms so small that one cannot earn enough. If a family’s 10 acres is split among four brothers, each gets 2.5 acres – hardly enough to prosper by traditional cropping. As one report observed, these dynamics have led to “a massive rise in the number of small and very small farms” and now “farms of under 5 hectares account for over 50% of total farmland area”. Without land consolidation or alternatives (like cooperative farming), the next generation sees little future on tiny plots.

- Lack of Credit and Modern Inputs: Young aspiring farmers also face difficulty accessing the resources needed to make farming profitable. Credit is a big one – banks in Pakistan have historically been reluctant to lend to small farmers, especially those without collateral (which most youth lack until they inherit land). While agricultural credit has expanded in recent years, it still reaches only a minority. Even after record disbursements, only about 2.86 million farmers received bank credit in FY2024 out of an estimated 8+ million farm households. This means a majority of small farmers operate without formal loans, relying on personal savings or informal lenders. A young person with an innovative farm idea (say starting a poultry farm or buying a tractor to offer services) will struggle to get a startup loan. One needs land title or asset guarantees which youth rarely have. Although the State Bank of Pakistan and government have schemes (e.g. interest-free loans for landless farmers, and a Credit Guarantee Scheme covering 50% of losses on small farmer loans), these programs have so far reached only a few hundred thousand farmers. The credit gap leaves many young farmers unable to invest in modern inputs – quality seeds, fertilizers, machinery, irrigation equipment – that could raise farm productivity and income. Similarly, access to technology and knowledge is limited. The public agricultural extension system in Pakistan is under-resourced; many farmers (especially younger, smaller ones) have little exposure to improved practices beyond what their family has always done. Without proactive outreach, they might not learn about new crop varieties, pest control methods or business skills that could make farming more attractive. Digital technology could be a game-changer – for instance, smartphone apps to get market prices or remote advice – but rural youth need connectivity and training to use such tools effectively. In many villages, patchy internet and low digital literacy impede this. Thus, lack of finance and tech access form a structural barrier that pushes youth to look for easier income sources outside farming.

- Rural Service Deficits and Lifestyle Factors: Another reason youth depart villages is the overall quality of life gap between rural and urban areas. Rural Pakistan lags behind cities in almost all human development indicators – education, healthcare, infrastructure, entertainment. For example, rural literacy is about 54% (and much lower for women) versus 76% in urban areas (2017 census data). Higher education opportunities in villages are scarce; a young person usually must relocate to get a college degree, and once in the city, they often settle there. Healthcare facilities in villages are limited to basic health units; anything serious requires travel to a town or city. Roads and transport in many rural localities are underdeveloped, making farm life feel isolating. Socially, villages offer fewer recreation options for youth – there are no malls, limited internet cafes or sports facilities, etc. All this contributes to a sentiment that “there’s nothing here for us.” Research on youth migration globally has found that “rural-urban differentials in the availability of social infrastructure (roads, schools, hospitals) influence migration decisions”. Pakistan is no exception: a talented village youth may want to stay and serve their community, but if the basic infrastructure for a decent life isn’t present, leaving becomes the rational choice. Additionally, rural areas often have more conservative social norms which some educated youth (especially young women) find restrictive – they might seek the comparative freedom of urban anonymity. The net effect is a cultural shift where farming and village life are seen as something to escape for anyone who has the education to do so.

Pull (and Potential Pull-Back) Factors – What Might Keep or Bring Youth in Farming

Despite all the above, certain factors could entice youth to either remain in or return to agriculture under the right circumstances. Not all rural youth aspire to leave; and of those who left, some do consider coming back if farming conditions improve or other options falter. Key potential “pull” factors include:

- Reality of Urban Unemployment: As noted, the urban job market often disappoints. A college degree does not guarantee a job, and many rural migrants end up in precarious positions. When youth face the harsh reality of city expenses and unemployment, some begin to rethink the value of their family’s land. For example, a young man who spends a few years job-hunting in Karachi may decide to return to his village in Sindh to help on the farm, realizing he can at least earn a living there. The high youth unemployment (over 11%) is thus a potential push-back factor – it discourages some from staying in cities long-term. In economic downturns, there have been instances of reverse migration: youths going back to rural areas when they couldn’t find work in town. Family elders sometimes remark that “if you can’t find a job, come back and take care of the land.” In the coming years, if Pakistan’s industries cannot absorb the growing youth labor force, agriculture might again become a safety net for employment. However, this is only a positive pull if farming can provide half-decent earnings; otherwise, it’s seen as a fallback of last resort.

- Ties to Family Land and Tradition: Emotional and familial ties do play a role. Many rural youth have a sense of attachment to their ancestral land and feel a responsibility to continue the family farming tradition (especially if they are the only son or the only one available to help aging parents). In more traditional communities, there is social pressure for youth to contribute to farming. For instance, in parts of KPK, farming is interwoven with notions of honor and duty. A young farmer from Kurram district explained, “[Farming] is our culture. When your family members are working on the farm and you are not helping them, you are considered a loafer (lazy)”. Such social expectations can pull youth into farming activities, at least part-time. They may still aspire for a non-farm career, but until that materializes, they’ll lend a hand on the farm out of respect for family. Even among educated youth, some do express a desire to improve their family farm rather than abandon it – they feel a sense of heritage tied to the land. If these cultural sentiments are reinforced with economic incentives, they could form a powerful pull. For example, a young man might take pride in being the one to modernize his grandfather’s farm with new techniques, thus balancing tradition with innovation. The key is that not all youth want to sever ties; many just want farming to be more rewarding if they are to pursue it.

- Emerging Opportunities in Agri-Business: A small but growing number of enterprising youth see agriculture as an opportunity for entrepreneurship, not just subsistence. These “agri-preneurs” are leveraging their education to identify niches in the agricultural value chain – whether it’s organic produce, dairy processing, farm-to-market logistics, or agricultural technology services. For instance, some tech-savvy youth have started platforms to connect farmers to markets (one startup provides an app for farmers to sell produce directly to urban buyers). Others have launched high-value crop ventures like mushroom farming, floriculture, or hydroponic vegetables targeting upscale markets. The success stories of such young agripreneurs can inspire peers. In fact, targeted programs have shown promising results. In one recent project, 700 rural youth and women in Punjab and Sindh received training in agribusiness skills (marketing, quality control, digital literacy), focusing on high-demand products like dried chillies, fruits, and animal fodder. The outcome was a 25% increase in their business revenues on average – demonstrating that, with the right support, young farmers can turn higher profits. As this project report noted, it provided “a sustainable pathway for women and youth out of poverty” while bolstering the agriculture sector. Such examples create a pull by showing that farming can be modern, innovative, and profitable. If more incubators, training, and financing become available for youth-led agricultural startups, we could see more educated youth choosing agribusiness as a career (much as they flock to tech startups today). The caveat is that this currently involves a minority of well-educated, entrepreneurial individuals – scaling it up would require systemic support (addressed in the next section on policy).

- Returning Migrants with Skills and Capital: Many of the youth who left – whether to cities or abroad – might return under certain conditions. For those who spent years working in Gulf countries, they often come back in their 30s or 40s with some savings. Traditionally, a lot of that remittance money is invested in buying more land or building a house in the village. These returnee migrants could become agents of agricultural revitalization if channeled properly. They have seen other countries (or at least other parts of Pakistan), may have picked up new ideas or work ethics, and crucially, they have capital to invest. Some progressive farmers in Pakistan’s villages are actually former migrants who, after years abroad, decided to put their savings into improved seeds, tractors, tube-wells, or dairy animals. Remittances already sustain many rural households – for example, families with a member abroad often use the money to hire laborers to work their land or to purchase better inputs, thus keeping the farm productive. If these returning youth were encouraged with matching grants or technical advice, they might transform their family farms into more profitable enterprises. Their presence can also alleviate labor shortages (one able young man can do the work of several elderly farmers). The key point is that not all who leave are gone forever; life events or disillusionment can bring some back. Making farming attractive and accessible for those returnees (so they don’t immediately try to go back abroad or to the city) is a potential win for the sector.

In essence, while the default trajectory now is youth moving away from agriculture, there are scenarios where that flow can be slowed or reversed. Unemployment and urban hardships can push some back; family and culture can hold some in place; and new opportunities in agriculture can pull some forward into farming by choice. The challenge for policy is to amplify these pull factors and mitigate the push factors. By doing so, Pakistan can hope to engage its educated youth in revitalizing agriculture. The next section outlines policy pathways to achieve this – concrete steps to transform perceptions, build skills, improve access to resources, enhance rural life, and foster innovation, so that farming becomes a genuinely viable and attractive option for the nation’s youth.

The Stakes

Why does it matter if youth abandon agriculture? The foregoing discussion hints at multiple risks. If the current trajectory continues – an aging farmer population, shrinking labor force, and stagnating farm sector – Pakistan could face serious consequences. Engaging youth in agriculture is not just a feel-good aspiration; it is critical for the country’s food security, economic development, and social cohesion. Here we outline what is at stake:

- Aging Workforce and Knowledge Loss: The average age of the agricultural workforce keeps rising, which can have negative implications for productivity and innovation. With over half of farmers above 50 years old, Pakistan’s farms are increasingly run by senior citizens. While experienced elders have invaluable knowledge, farming is physically demanding and often benefits from quick adoption of new ideas – attributes generally more associated with youth. An aging farmer population means there is less physical stamina available for labor-intensive tasks and potentially less openness to trying new techniques or crops. As older farmers retire or pass away, their farms may not have a prepared successor if their children have moved away. This could lead to land being left fallow or sold off. Moreover, rural youth exodus can mean a loss of local knowledge transfer – traditionally, skills are passed from one generation to the next on the farm, but if the next generation is absent, that chain is broken. A FAO analysis warns that the “farming sector is ageing rapidly” and without youth, even existing knowledge and good practices may fade as elders age out. In short, the human capital base of agriculture is eroding. If no young farmers are in the pipeline, who will grow Pakistan’s food 20–30 years from now? It’s a looming generational crisis.

- Labor Shortages and Higher Costs: Several areas already report difficulty finding farm labor during peak seasons. Younger villagers used to serve as the workforce for planting, weeding, and harvesting on larger farms or as sharecroppers; now many of them are gone. The gap is sometimes filled by migrant labor from even poorer regions (for instance, laborers from southern Punjab travel to central Punjab for the wheat harvest, or Afghan migrants take up farm work). But as overall rural population growth slows and urban opportunities beckon, agriculture could face systemic labor shortages – an ironic situation in a country with millions of underemployed youth. A case study in Kurram noted that many fields went uncultivated during conflict and after, because “farmers could not bring their products to market or buy inputs… conflict forced many people, especially the youth, to flee… [remaining] youth were less interested in farming”, resulting in acute labor deficits. While that was conflict-driven, other regions see similar effects from economic migration. When labor is scarce, its cost rises; farmers have to pay more to hire help, which squeezes their margins and can lead them to reduce cultivated area or switch to less labor-intensive crops. Some Punjab farmers, for example, have reduced cotton planting (which requires a lot of picking labor) in favor of wheat or mechanized crops, due in part to labor availability issues. If this trend continues, yields and production could suffer – crops might not be sown or harvested on time, and some land could be abandoned. This also has implications for rural wage earners: those who do want farm jobs may benefit from higher wages in short-term, but if farmers decide to mechanize or quit due to high labor costs, those jobs disappear entirely. It’s a lose-lose spiral of rural employment.

- Stagnating Productivity and Innovation: Young farmers are often considered more likely to adopt new technologies and practices – whether it’s experimenting with a new seed variety, using a smartphone app for farm advice, or trying precision farming techniques. They also tend to be better educated. Losing youth from agriculture thus threatens to slow down the sector’s modernization. A commentary on rural youth migration observed that “the departure of youth also stifles innovation within agriculture. Younger generations tend to be more open to adopting modern technologies”. Many of the breakthrough revolutions in farming globally (from the Green Revolution to today’s digital farming) rely on energetic, curious farmers willing to try something different. If Pakistan’s farms are predominantly in the hands of 60-year-olds, the diffusion of innovations like biotech seeds, drones for crop monitoring, or climate-smart practices may be much slower. This productivity risk comes at a time when innovation is badly needed – climate change is making farming tougher (witness the 2022 super-floods and frequent droughts), and global competition is rising. An agriculture sector without youth is in danger of becoming static, just maintaining traditional methods. That could cause yields to flatline or even decline relative to potential. Already we see signs of stagnation in yields of major crops, as discussed earlier. Reinvigorating growth in output per hectare may well depend on engaging tech-savvy youth who can leverage new knowledge. Without them, Pakistan risks falling behind in agricultural productivity, which in turn affects overall economic growth since agriculture supports downstream industries (textiles, food processing).

- Food Security and Import Dependence: If domestic agriculture cannot keep pace with population and demand, Pakistan’s food security is at risk. The country’s population is projected to reach 260+ million in the next decade, adding millions of mouths to feed. Yet cropped area has not expanded commensurately, and yield gains have been modest. The result has been increasing reliance on food imports to fill the gap. In FY2023, Pakistan’s food import bill was about $9 billion – including massive imports of wheat, cooking oil, pulses, and tea. (Half of that was edible oil alone, as local oilseed production is meager.) While trade can complement food supply, heavy dependence on imports leaves Pakistan vulnerable to global price shocks and trade disruptions. We saw this during the 2022–23 period when international wheat and oil prices spiked; domestic food inflation hit record highs. If the farming workforce continues aging and shrinking, domestic production of staples like wheat, rice, and vegetables may stagnate or decline, widening the food deficit. Already, Pakistan, once nearly self-sufficient in wheat, has become a net importer in some recent years due to production shortfalls. Fish and meat supply could also lag growing demand if fewer youth take up livestock rearing. Food security isn’t just about total output but also about who produces – a dwindling number of old farmers cannot indefinitely feed a growing young nation. There’s also the issue of strategic food autonomy: policymakers worry that over-reliance on imports for essential grains or oilseeds is a strategic vulnerability. Without engaging youth in boosting agricultural output, Pakistan may face more frequent food crises or be forced to spend scarce foreign exchange on imports, which hurts the overall economy.

- Widening Rural Inequality and Social Upheaval: The exodus of youth could exacerbate inequality on multiple levels. Between rural and urban: if rural areas are emptied of dynamic youth, their economic decline relative to cities could accelerate. Villages might sink into poverty and stagnation, while urban wealth grows – leading to a deeper rural-urban divide. This could fuel social resentment or instability. Within rural areas: as small farmers struggle or leave, who takes over their land? Often it’s big landowners or outside investors (sometimes corporations) who consolidate landholdings. Pakistan is actively exploring large-scale corporate farming to boost output, which has some benefits, but it could come at the cost of marginalizing smallholders. As one analyst warned, “Large-scale corporate farms could reduce the market share of small farmers as they struggle to keep up”. If youth from small-farm families are not empowered to continue farming, those families may end up selling or leasing their land to wealthier entities. Land consolidation might improve efficiency, but it also means the profits of agriculture accrue to a smaller elite. Rural income inequality is already significant – a small fraction of landlords control a big chunk of land (e.g. over 90% of farmers have less than 12.5 acres, while the remaining under 10% own most of the land area). Youth flight could worsen this, as more land falls into fewer (corporate) hands. Unemployed or landless rural youth might then only find work as low-paid labor on large farms or end up landless in urban slums. Social structures in rural areas could fray – traditionally, small farmers are the backbone of village communities and local leadership (e.g. in water management, cooperatives, etc.). If they disappear, rural society could stratify into large landowners and a laboring class, with many youth simply gone. Such inequality and disenfranchisement carries the risk of rural unrest or increased crime/drug use among those left behind with no stake. Lastly, gender inequality could increase if progressive young men and women leave, leaving conservative elders in charge – rural women might be further deprived of voice and opportunity in an aging farm society. All told, the social fabric of rural Pakistan is at stake. Keeping youth in farming – and enabling them to succeed – would inject hope and reduce the desperation that drives destabilizing inequality and migration.

In sum, the stakes are high: an agricultural sector without youth is one on a path of slow decline – risking lower production, less innovation, labor bottlenecks, greater import dependence, and entrenched inequalities. Conversely, if Pakistan manages to harness the energies of its educated youth for agricultural transformation, it can secure its food future, boost inclusive growth, and stabilize rural communities. The next section discusses how to realize that positive scenario. There is no single silver bullet, but a mix of policy pathways can create an environment where young people want to engage in agriculture – as modern agripreneurs, skilled producers, and innovators leading Pakistan’s next Green Revolution.

Policy Pathways

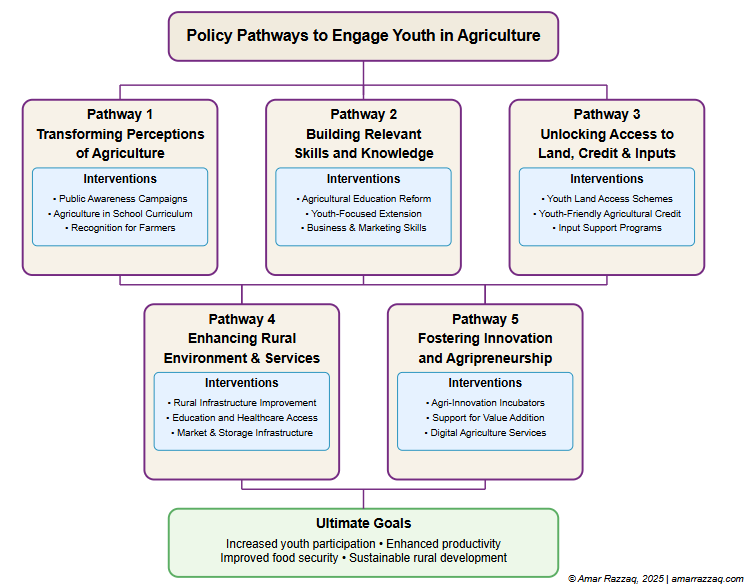

Re-engaging youth in agriculture requires reversing deeply entrenched perceptions and lowering real barriers. It calls for policy action on multiple fronts, from changing mindsets to providing material support and improving rural living conditions. Below are five strategic pathways – complementary and mutually reinforcing – to make agriculture a viable and attractive pursuit for Pakistan’s educated youth:

1. Transforming Perceptions of Agriculture

A fundamental task is to change the narrative around farming so that it is seen as a progressive, respected and profitable profession. As long as farming is viewed as a “dead-end” or second-class career, convincing young people to pursue it will be an uphill battle. The government, media, and educational institutions must collaborate to elevate the status of agriculture in the public imagination. This can be done by highlighting success stories, integrating agriculture into education, and launching campaigns that resonate with youth aspirations:

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Just as past media campaigns changed perceptions about issues like literacy and health, we need campaigns that portray farming in a positive light. This could include television segments showcasing young, innovative farmers who have made farming prosperous with new techniques (for example, a youth who started an organic farm supplying high-end supermarkets, or one who introduced solar-powered irrigation on his farm). Social media can be a powerful tool here – short documentaries or YouTube series can profile “Agri-Influencers” (young farmers or agri-entrepreneurs) and demonstrate that farming today involves skill, technology, and entrepreneurship. The aim is to provide role models for rural youth. When youngsters see peers their age making a mark in agriculture, it can shatter the stereotype that farming is only for those who have “no other option.” Officials could also partner with popular cultural figures to endorse farming – e.g. a famous cricket star or actor visiting a model farm and talking about the importance and pride of agriculture.

- Agriculture in School Curriculum and Clubs: Attitudes are shaped young. Introducing agriculture-related education in schools (especially rural schools) can foster curiosity and respect for farming. This doesn’t mean turning all students into farmers, but basic agricultural literacy – understanding where food comes from, the science of plants/soil, and the business of farming – can be taught as part of science or social studies. More importantly, experiential learning opportunities like 4-H clubs or “Young Farmers” clubs in high schools could be promoted. These clubs can engage students in gardening, animal rearing, or small agri-business projects as extracurricular activities. Many countries have such youth programs that cultivate interest in agriculture early on. For instance, a school could maintain a vegetable plot managed by students, with a local ag extension officer as an advisor. Competitions can be held for best youth farming project, with prizes and recognition (imagine a “Youth Agri-Champion” award at district level). The federal and provincial agriculture departments, along with education departments, should collaborate on pilot programs in this vein.

- Respect and Recognition for Farmers: Government leaders can set the tone by publicly celebrating farmers’ contributions. Pakistan already observes a “Kissan Day” (Farmers’ Day) on December 18; this could be expanded with specific focus on young farmers. Scholarships or fellowships could be established for outstanding young farmers to pursue further training (similar to how we reward top students in academics). Additionally, ensuring that farmer voices (including youth) are represented in policy dialogues and media panels will signal that their expertise is valued on par with industrialists or white-collar professionals. The language used in discourse matters too – avoiding derogatory stereotypes and emphasizing that farming today involves knowledge of STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) could help. Essentially, farming needs to be “rebranded” as a modern profession. Tailored educational programs and outreach can help here – FAO notes that providing youth with educational programs specific to agriculture can re-engage them. This might include short courses on agri-entrepreneurship offered to college grads or diploma courses in high-tech farming for rural youth. When young people see that one can go to school for agriculture and build a career, it legitimizes the field.

Changing perceptions is a slow process, but it underpins all other efforts. If done right, within a decade we could have a cultural shift where an agriculture graduate or a young farm owner is seen with the same respect as an engineer or banker, and where parents no longer say “don’t be a farmer” but rather “if you farm, be the best at it with new knowledge.” In conjunction with the concrete support discussed next, this could make a real difference in drawing educated youth to agriculture.

This policy framework addresses Pakistan's youth exodus from agriculture through five strategic pathways, creating a comprehensive approach to transform farming into an attractive, viable career option for educated young people. © Amar Razzaq, 2025

2. Building Relevant Skills and Knowledge

Even if attitudes improve, youth will only succeed in agriculture if they have the skills and knowledge needed for modern farming and agribusiness. Thus, a critical policy pathway is strengthening education, training and extension services to equip young people with the technical and entrepreneurial skills to thrive in agriculture. This involves updating curricula, expanding vocational training, and leveraging modern methods to reach rural youth:

- Revitalize Agricultural Education: Pakistan has a number of agricultural universities and colleges (e.g. in Faisalabad, Tandojam, Peshawar, Rawalpindi, Lasbela). These institutions should be supported to update their curricula to reflect current and future needs (such as precision agriculture, value chain management, climate-smart agriculture). More importantly, access to agricultural education should be broadened. Establishing polytechnic institutes or community college programs in rural areas that offer diplomas in practical fields like farm management, horticulture, dairy technology, etc., would allow rural youth who may not go for a full university degree to still get formal training. For example, short 6-month courses in poultry farming or drip irrigation techniques can impart valuable skills. Government can subsidize such courses for youth from farming families. Additionally, integrating some agricultural modules into general education for rural schools (as mentioned in Pathway 1) builds foundational knowledge. The goal is a skilled young farmer cadre that knows both the science (e.g. pest control, soil health) and the economics (marketing, accounting) of agriculture.

- Youth-Focused Extension and Training Programs: Traditional extension services often focus on older male landowners, via methods like village meetings or demo plots. To engage youth, extension must innovate. One approach is to recruit and train young extension agents – women and men in their 20s who can better communicate with rural youth and serve as peer mentors. For instance, a program could select educated rural youth, train them intensively in new farming techniques, and have them serve as “village resource persons” who advise fellow farmers (a train-the-trainer model). Digital tools are also key. Many rural youth do have smartphones; agriculture departments and NGOs can develop e-learning modules, YouTube tutorials in local languages, or even mobile games that teach agronomic concepts. Setting up “digital hubs” at village level (perhaps at schools or ag service centers) where youth can access the internet to follow online courses or tutorials about farming could merge tech with agriculture. Collaborations with initiatives like Coursera or edX to offer free online courses in agriculture (with local study groups) can be explored. Evidence shows that targeted training improves outcomes: entrepreneurial training for rural youth in Pakistan has been found to reduce business failures and increase incomes. One example is the Standard Chartered “Agripreneurs” project which provided business training to hundreds of young farmers, resulting in significant revenue increases. Scaling up such programs nationally – possibly via public-private partnerships – could empower thousands of aspiring young agripreneurs.

- Practical Exposure and Internships: There is often a gap between theoretical knowledge and hands-on experience. Creating opportunities for young people to “learn by doing” is vital. This could include farm apprenticeship schemes where urban-educated youth interested in farming spend time working on model farms or research stations to gain experience. Likewise, encourage established progressive farmers to take on youth interns/mentees. The government can incentivize this by covering a stipend for interns. Agricultural research institutes can involve youth in participatory research (citizen science approach) – for instance, having young farmers test experimental seed varieties on their fields in collaboration with scientists, thereby giving them early exposure to innovations. Another idea is organizing Youth Farmer Field Schools, which has been done in some countries: groups of young farmers meet regularly through a cropping season, guided by an extension facilitator, to learn by observing and managing a demonstration plot collectively. They learn experimentation and decision-making in a group setting, which builds confidence and skills.

- Business and Market Skills: Beyond production, youths need skills in marketing, processing, and other downstream aspects to really make farming profitable. Thus, training shouldn’t just be “how to grow crop X” but also “how to sell crop X for the best price” or “how to add value to product X.” Workshops on basic accounting, packaging, branding, and use of digital marketplaces can turn farmers into entrepreneurs. In the Agripreneurs project mentioned, participants got training in marketing, quality assurance, and digital literacy, which helped them tap higher-value markets. Expanding such training through farmer cooperatives or rural youth clubs could allow even those not formally educated to gain business savvy. Micro-entrepreneurship training could also cover how to start side businesses like agri-tourism (e.g. farm stays), farm mechanization services (renting out a tractor), or food processing cottage industries. Coupled with microfinance, this can open new income streams for rural youth.

- Leveraging Veteran Knowledge: While focusing on new skills, we shouldn’t ignore the wealth of knowledge older farmers have. A mentorship program can pair willing experienced farmers (“lead farmers”) with youth who are starting out. The older mentor can guide on local best practices, while the youth can assist with labor and maybe introduce new ideas – a two-way learning. This can help bridge the generation gap and ensure traditional knowledge is passed on, but in a context that also embraces new methods.

In summary, building youth capacity for agriculture means a skill revolution at the rural grassroots. If a young person is armed with the know-how to run a farm as a business, proficient in modern agronomy, and connected to sources of information, they are far more likely to give farming a serious shot. Pakistan needs to invest in its human capital through agricultural education and training reform, much like it invests in STEM education for industrial jobs. The returns could be immense in terms of productivity and rural employment.

3. Unlocking Access to Land, Credit and Inputs

Even a willing and skilled young farmer cannot get far without access to the basic resources of production: land to cultivate, capital to invest, and inputs/technology to improve productivity. Therefore, policies must break down the barriers that currently lock many youth out of these resources. Key interventions include land reforms/initiatives to get land into the hands of young cultivators, financial inclusion measures, and facilitating access to modern inputs and equipment:

- Land Access Schemes: While comprehensive land reform (redistribution of large estates to landless) has long been stalled in Pakistan due to political resistance, there are other ways to improve youth access to land. One approach is creating a land bank or land lease program for youth. For example, the government could identify underutilized public land or recovered state land and allocate it to young farmers on long-term lease at nominal rents, provided they bring it under cultivation. This was proposed by peasant organizations – “state land be redistributed among landless peasants, rural poor, women, youth” – and could be piloted in certain areas. Another mechanism is facilitating land leasing markets: many small landowners who migrate or cannot farm might be willing to lease out their land, but lack of trust and legal frameworks inhibit leasing. Government or cooperatives could act as intermediaries to connect landless youth with landowners for secure lease agreements, perhaps with initial subsidies. A “Youth Farm Lease Scheme” could, for instance, pay part of the lease cost for the first 2 years as the young farmer establishes the business. Additionally, simplifying inheritance and co-ownership laws could allow siblings to consolidate or allocate land more rationally rather than fragment it. For instance, offering incentives for family members to pool their inherited land into a single holding operated by one of them (with others as shareholders) could prevent tiny splits. Group farming models can also help – if five rural youth each have 2 acres from their families, they could form a joint venture to farm 10 acres together, sharing costs and profits. Extension services can promote such collective farming among youth groups. Ensuring women’s access to land is also crucial, as many young women in rural areas are involved in farming but rarely hold land titles. Programs to give joint spousal titles or allocate state land to female farmers (with support for operations) would tap into an overlooked youth segment.

- Youth-Friendly Agricultural Credit: Expanding credit to young and new farmers is essential. Banks typically require collateral and credit history, which young people lack. The government and SBP should strengthen schemes that encourage lending to this demographic. The Credit Guarantee Scheme for Small and Marginal Farmers (CGSMF) already provides 50% risk cover to banks for small farmer loans – this can be scaled up, with a special quota for loans to under-30 farmers. Since 2016, only ~150,000 farmers benefited from CGSMF; millions more could. The scheme could be supplemented with interest-rate subsidies or interest-free tranches for youth (the government’s recent initiative of Interest Free Loans & Risk Sharing for landless flood-affected farmers is a good model). Another idea is to create a dedicated “Youth in Agriculture” financing window under the PM’s Youth Program, which already gives small business loans to youth. Allocating a percentage of those loans specifically to agriculture (for purchasing livestock, seeds, small machinery, etc.) at low interest and with flexible repayment can lower the entry barrier. Microfinance institutions and rural support programs should also be incentivized to target rural youth with tailored products (e.g. group lending where a group of youth collectively guarantee each other’s loans). Moreover, innovative financing like value-chain financing (where agribusiness companies provide inputs on credit to contract growers and deduct at purchase) can be leveraged to support young farmers who enter into contract farming arrangements for e.g. food processors or exporters. As digital payments and mobile banking spread, even unbanked youth can start accessing financial services – for instance, using mobile wallets to receive crop sale proceeds or credit disbursements. By making credit accessible, we enable youth to invest in all the things that make farming viable: quality seeds, fertilizer, irrigation, etc. Without credit, a young farmer basically can only do what his forefathers did – which likely isn’t profitable enough to keep him interested.

- Subsidies and Input Access for Young Farmers: To encourage new young entrants, the government could offer targeted input support. For example, “Young Farmer Starter Kits” – a one-time subsidy package consisting of seeds, fertilizers, perhaps a small irrigation pump or sprayer, and training – could be given to youth who take up farming formally (either on their own land or leased). Some provinces have provided Kissan Cards (subsidy cards) to farmers; extra top-ups could be given on these cards for farmers below a certain age to reduce their input costs. Access to water is critical too – schemes to subsidize tube-well installation or water storage for young farmers in water-scarce areas would be helpful. Machinery is another big ticket item: while one may not give a tractor free, mechanization pools or rental centers can ensure youth farmers can rent tractors, threshers, laser levelers, etc., at affordable rates when needed. The government or cooperatives can set up custom hiring centers in rural areas (some exist) – these should specifically reach out to small/young farmers who can’t afford equipment otherwise. Electronic Warehouse Receipt systems being implemented (where farmers can store produce and get a loan receipt against it) should be promoted among youth to improve their access to post-harvest finance and better prices (they can avoid forced selling at low prices). In summary, a combination of financial inclusion and input provision lowers the risk for youth to try farming and helps them overcome the initial capital hurdle.

- Land Tenure Security and Legal Support: Youth who lease or sharecrop land often face insecurity – a landowner could kick them off after one good harvest. Implementing or reinforcing laws that protect tenant farmers and sharecroppers (e.g. guaranteeing them a contract of at least 3–5 years and fair crop share) would make farming more attractive to those without land. Also, simplifying registration for producer groups or cooperatives can allow youth to collectively own assets or enter contracts, giving them more bargaining power and scale. Providing legal literacy and support to young farmers (perhaps via rural organizations) can help them navigate land records, contracts, and avoid exploitation.

By unlocking resources, we basically empower youth to actualize their farming ideas. When a trained, enthusiastic young person has access to a few acres of land, credit lines, and good inputs, they have the ingredients to succeed. Pakistan’s policies should thus aim to turn the currently “resource-poor” young farmer into a “resource-enabled” entrepreneur. Many countries have done similar initiatives (for example, Turkey and Malaysia have programs granting land and start-up capital to young farmers); Pakistan can tailor such ideas to its context.

4. Enhancing the Rural Environment and Services

Making agriculture appealing to youth is not only about what happens on the farm, but also about the quality of life in rural areas. To retain young people, villages must become places where one can live a decent life, not be deprived of amenities and opportunities. This means investing in rural infrastructure, services, and development so that rural youth do not feel they must move to the city to enjoy modern conveniences or basic services. Key actions include:

- Improve Infrastructure (Roads, Electricity, Internet): Good roads connect villages to markets, reduce transport costs, and also make rural life less isolating. Continued expansion of farm-to-market roads and upgradation of existing rural roads is vital – so a farmer can drive produce to town quickly, and youth can commute or travel easily. Electrification in Pakistan’s rural areas is widespread on paper, but reliability is an issue – frequent outages affect agro-processing and home life. Strengthening rural power supply (and promoting off-grid solar where grid is unreliable) can power water pumps, cold storage, and also household needs (fans, lighting, phone charging) that improve daily life. Internet and telecom connectivity is a game changer for youth. The government should push for mobile broadband coverage to reach remote villages (collaborating with telecom companies, possibly with subsidies or USF – Universal Service Fund – projects). If a young farmer can use WhatsApp, YouTube, or Facebook from their village, they stay connected with the world and can even do side gigs online. High-speed internet also enables e-learning and e-commerce from rural areas. A target could be set like “90% of villages on 3G/4G network by 2025.” As one FAO study noted, bridging rural infrastructure gaps (roads, schools, hospitals) is crucial to addressing the root causes of youth migration. Pakistan should integrate rural infrastructure upgrades as part of its youth and agriculture strategy, not see it separately.

- Education and Health Services Locally: Strengthening rural schools (especially secondary schools) can encourage families to stay and invest in their children’s future without migrating. Many rural high schools lack science labs, good teachers, or even go up to grade 10 only. Investing in quality education in rural areas – including vocational streams related to agriculture in high school – will produce more skilled youth who can innovate locally. Similarly, improving rural healthcare (posting doctors to union council-level facilities, telemedicine options, etc.) means young families feel more secure living in villages. If every tehsil has a well-functioning hospital and every village cluster has a clinic, people don’t have to rush to cities for medical needs. These services also create local employment (e.g. teachers, nurses) which can keep educated youth (especially women) in rural communities.

- Rural Amenities and Youth Engagement: One often overlooked aspect is providing recreational and cultural opportunities for rural youth. Small investments like setting up sports facilities (cricket grounds, volleyball courts) or community centers with libraries and internet access can greatly enhance rural youth’s quality of life. Youth clubs can organize sports leagues, debates, skill workshops – giving young people a sense of community and personal growth in their hometowns. District administrations and local governments should be encouraged (and funded) to run youth programs in rural areas, just as cities have youth festivals. When rural youth feel heard and see avenues for personal development locally, they are less inclined to think that only a city can fulfill their aspirations. Even simple things like supporting rural transport (so youth can travel to nearby town for leisure or classes and return the same day) matter. Government might revive schemes like student buses for rural colleges, etc.

- Functional Markets and Storage: From an agriculture perspective, having local produce markets and storage facilities benefits farmers and can also create a bit of rural vibrancy. If a young farmer knows they can easily take produce to a nearby mandi (market) and get fair prices (through transparent auctions or digital market information displays), they might find farming more rewarding. Additionally, if rural towns have more agro-processing units (mills, dairy chilling centers, etc.), they offer local non-farm jobs and also strengthen the linkage for farmers to sell goods. This kind of rural agro-industrial development (e.g. setting up small processing plants via public-private efforts in milk surplus villages, or packhouses for fruits in producing areas) keeps value addition in rural areas, creating employment that can keep youth in their communities. It’s a virtuous cycle: better rural infrastructure and services attract small industries, which then create jobs and improve incomes, making rural life more attractive.

- Safety and Security: Another aspect is ensuring law and order in rural areas. Some young people leave because of rural insecurity (e.g. in parts of interior Sindh or Balochistan, issues of tribal conflict, crime, or feudal oppression can be acute). Strengthening policing, dispute resolution mechanisms, and governance in rural areas will make them safer and more welcoming for educated youth who might otherwise fear being stuck in a backwards or unsafe environment.

In essence, narrowing the rural-urban gap in living standards is key to convincing youth that they need not flee to a city to have a decent life. Rural development should be youth-centric: ask what would make a young person content to live and work here? Many of the answers (internet, sports, education, health, roads) are basic development goals that Pakistan has been pursuing, but prioritizing them in high out-migration areas could yield direct benefits in retaining talent. When a village is “livable” in a modern sense, farming there becomes a much more attractive proposition.

5. Fostering Innovation and Agripreneurship

Finally, to truly revitalize agriculture with the help of youth, Pakistan must create an ecosystem of innovation and continuous learning in the rural sector. Young people are naturally more inclined to experiment and start new ventures if given the chance. The government and private sector can catalyze this by supporting agripreneurship, research, and knowledge networks that actively involve youth. This pathway builds on skills and resources, but goes further to encourage leadership by young innovators in agriculture:

- Innovation Incubators and Competitions: Establish agri-innovation incubators or hubs where young entrepreneurs can develop agri-tech and agribusiness ideas. Universities and provincial agriculture departments can set up incubator centers in farming regions (for example, an incubator at the University of Agriculture Faisalabad, or one in partnership with a chamber of commerce in Hyderabad) that provide mentorship, technical advice, and even small grants to youth-led startups targeting agriculture. These startups could range from mobile apps for farmers, to food processing enterprises, to farm equipment fabrication. Regular innovation challenges or hackathons can be held to crowdsource ideas from youth – e.g. a “Smart Farming Hackathon” inviting young techies and agri students to prototype solutions for farm problems (better irrigation control, pest monitoring, etc.). Winners could get seed funding or partnerships with government projects to implement their solutions. Such initiatives send a message that agriculture is a dynamic field where innovation is happening. Some young Pakistanis have already pioneered things like sensors for soil moisture or drone spraying services; an enabling environment would multiply these. The involvement of youth in R&D is crucial – research institutes should recruit young scientists and also involve young farmers in on-farm trials and feedback loops.

- Youth Extension Corps and Knowledge Sharing: We touched on integrating youth into extension as trainers, but it’s worth emphasizing the creation of a Youth Agricultural Corps – a cadre of educated youth employed (even on stipend) to spread new knowledge and facilitate adoption of innovations in farming communities. This could be part of a national service program: agriculture graduates or passionate young farmers could devote e.g. two years to work in underserved districts, disseminating techniques like laser land leveling, new crop rotation, or livestock care practices. This not only helps farmers but also gives those youth experience and purpose. Alongside formal extension, peer-to-peer learning networks among young farmers should be fostered. Government or NGOs can sponsor exchange visits – taking a group of young farmers from, say, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to Punjab’s progressive farms to learn, or vice versa. Young farmers seeing innovations first-hand in another region often come back inspired to implement them. Creating online forums or WhatsApp groups moderated by agronomists where young farmers can ask questions and share experiences is another low-cost knowledge-sharing tool.

- Incentives for Youth-Led Value Addition: Many rural youth could profitably engage in adding value to raw farm produce if supported. For example, instead of selling milk at low rates, a group of youth might start a small cheese-making unit; or instead of raw mangoes, make dried mango slices for export. To encourage this, the government can provide small grants or matching funds for youth agripreneurs who set up processing, packaging, or direct marketing ventures. Tax breaks or reduced interest loans for agri-processing startups owned by young individuals could also help. Each province could hold an annual Agripreneur Summit where young innovators showcase their agri-products and connect with investors/markets. This creates excitement and motivation around agri-based entrepreneurship. The private sector (agribusiness firms, food companies) should also be roped in to support youth – e.g. through out-grower schemes that deliberately include young farmers, or contracting youth-led businesses in supply chains.

- Research and Development for Youth Priorities: Direct research efforts to issues that matter for small/young farmers – like low-cost technologies, climate-resilient crop varieties for small plots, labor-saving tools. Including youth representatives in research priority-setting (say, in PARC – Pakistan Agricultural Research Council – programs) can align innovations with what the next generation of farmers needs. Furthermore, encouraging student research projects on real farm problems can yield innovative solutions; a funding stream for final-year ag students or young scientists to do on-farm research in collaboration with farmers would both build capacity and solve practical issues. For instance, a group of young scientists might work on an integrated pest management plan for a village’s crops and demonstrate its success, building trust in science among farmers.

- Leveraging ICT (Information & Communication Tech): Pakistan’s youth are quite adept with smartphones. Government can deploy more digital services for agriculture: SMS or app-based early warning systems for weather/pests, mobile banking for transactions, e-marketplaces for inputs and outputs that youth can easily use. A centralized but youth-friendly platform – perhaps a “Digital Kissan Hub” app – could combine advisory, marketing, and credit info in one. When farming integrates with tech, it naturally appeals more to younger folks who enjoy using gadgets and apps. Some private startups (e.g. those providing farm advisory via SMS) exist; scaling these in partnership with telecom companies could give every young farmer a “tech toolbox” in their hand.

- Aligning Policy and Institutions to Include Youth: Ultimately, institutional support must endure. Ministries of agriculture (federal and provincial) should institutionalize youth focus – maybe a dedicated Youth in Agriculture unit that coordinates all these initiatives and tracks progress. Youth should also have a seat at the table in policy formulation. For example, involving young farmer representatives in the Agricultural Credit Advisory Committee or in commodity boards would ensure their perspectives inform decisions (the SBP has started focusing on underserved areas via Champion Banks; similarly, focus on underserved demographics like youth could be sharpened). International agencies like FAO and IFAD are keen to support youth empowerment in agriculture; Pakistan can leverage their expertise and funds by aligning local initiatives with global programs. In fact, FAO’s evaluation noted that FAO Pakistan had not yet had a strong programmatic focus on youth engagement – a gap that can be rectified by new collaborative projects targeting rural youth employment.

In summary, fostering innovation means making agriculture exciting and dynamic – something young minds can find challenge and reward in. When youths see that they can be creators and leaders in this field – invent a tool, start a brand, solve a local problem – it imbues farming with a sense of purpose beyond just tilling the land. Pakistan’s youth are brimming with ideas and energy; channelling even a fraction of that into agricultural innovation could unleash a new era of growth. As one commentary put it, small-scale agriculture can be “ecologically rational, socially just, and capable of absorbing unemployed youth” – but only if we make it a hub of creativity and opportunity, not drudgery.

Conclusion

Pakistan stands at a critical crossroads in terms of demographics and development. The nation’s youth bulge – millions of young people aspiring for a better life – can either become a demographic dividend or a source of social strain. At the same time, agriculture – the age-old backbone of the economy – is in need of rejuvenation and innovation. The convergence of these challenges actually presents a powerful opportunity: engage the youth to transform agriculture, and in doing so, secure both their futures and the country’s food future. This policy commentary has outlined how and why Pakistan must act with urgency to make farming and agribusiness attractive to its educated youth.

To recapitulate, the current trajectory of youth migrating away from farms is unsustainable. It is leaving behind an ageing agricultural workforce, causing labor shortages in villages, and threatening to stagnate productivity at a time when we need to increase food production. If nothing is done, Pakistan risks greater food insecurity, heavier reliance on imports, and deeper rural poverty and inequality. Conversely, if even a portion of young Pakistanis can be productively absorbed into agriculture, it would inject much-needed energy, ideas, and labor into the sector. It would help ensure that as older farmers retire, a new generation is ready to take the reins – armed with better education and technology than ever before.

The solutions span multiple domains, but they are interlinked. Changing mindsets is the first step – convincing young people that farming can be “cool” and respected, and convincing society to value farmers. From school classrooms to TV screens, the narrative must shift to celebrating the farmer as a national hero (after all, without farmers, there is no food security). Next, equipping youth with skills through revamped education and training will give them the confidence and competence to try modern farming – whether it’s precision agriculture or agribusiness management. Then, opening up access to land and finance will remove the practical barriers that currently keep willing youth from starting up in agriculture. We must ensure that lack of collateral or land does not kill the dreams of an aspiring young farmer – measures like youth land leasing, credit guarantees, and input subsidies are critical in this regard. Parallel to this, investing in rural infrastructure and services will make villages liveable and vibrant, so that educated youth do not feel compelled to flee to cities for every need. And finally, by fostering a culture of innovation in agriculture, we make it intellectually and financially rewarding for youth – allowing them to be creators of new solutions, not just labourers following old ways.

None of these paths is easy; they require political will, funding, and coordination across ministries and sectors. But the payoff can be immense. Engaging youth in agriculture is essentially a win-win strategy: it fights youth unemployment by creating jobs in farming and its value chains, and it boosts agricultural development by filling it with energetic human capital. It also addresses rural-urban imbalance by channeling investment and attention to rural areas. Importantly, it gives youth a stake in the country’s future – rather than feeling neglected and looking to go abroad, they can become stakeholders in Pakistan’s progress, as owners of enterprises and stewards of the land.